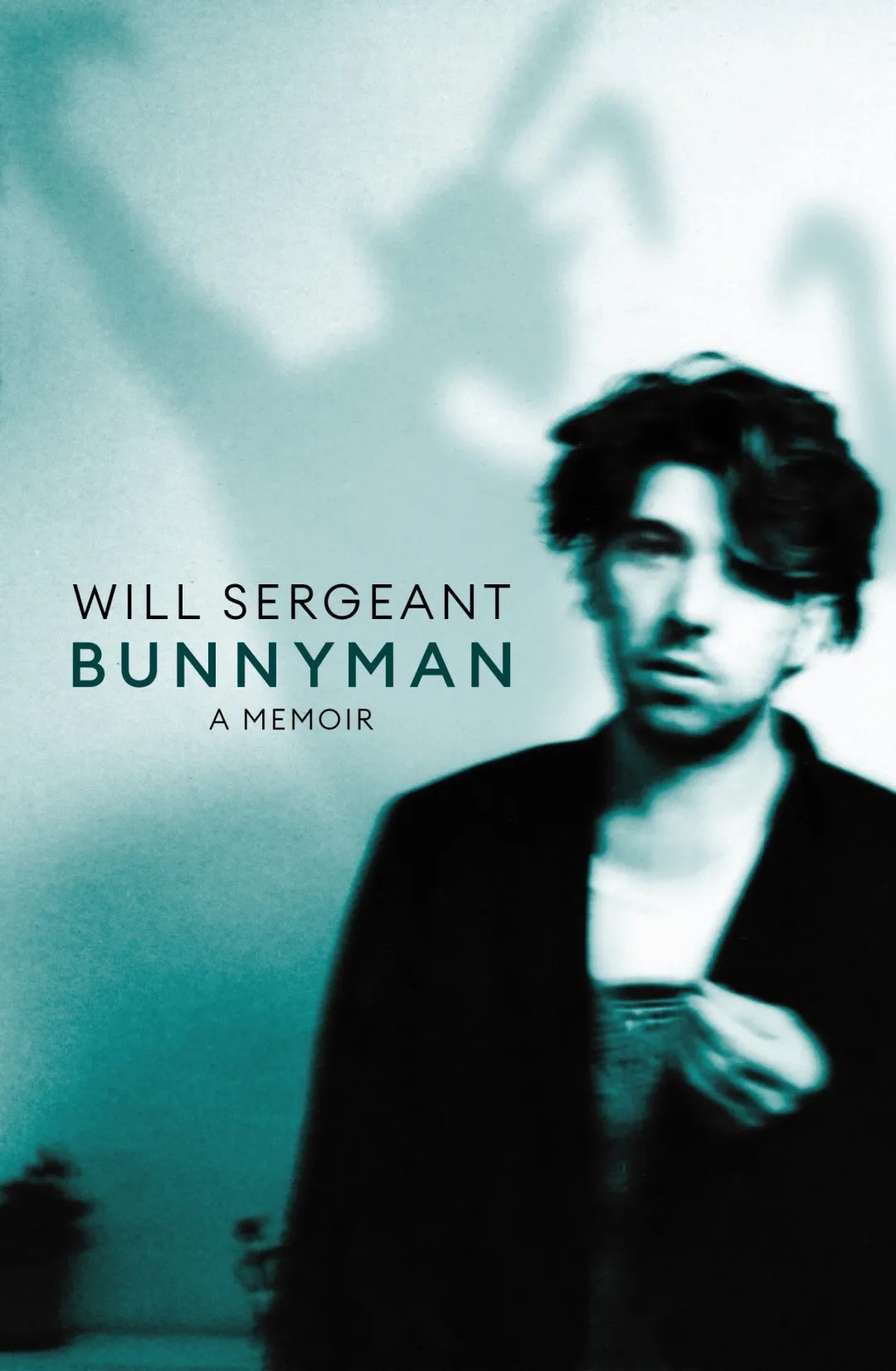

Will Sergeant never considered himself a writer. “I was rubbish at school. I wasn’t interested in English at all or anything like that. I’m rubbish at writing. When at school, I used to just write any old crap just to get through. It would just be scribble. They’d be like, ‘What the hell’s this?’” he says with a laugh, on the irony of writing one of the year’s most lauded rock ‘n roll memoirs. The Echo & the Bunnymen guitarist seems awed by the book’s glowing reception: “It’s been in all kinds of books of the year lists and stuff in papers and websites and podcasts of people, and stuff like that,” he smiles.

Bunnyman is the history lesson we didn’t know we needed.

Born in 1958 in a post-war Britain, Sergeant strings together vivid and often distressing snippets of growing up in an ordinarily combative, low-income and depressed Liverpool, all laced together with compassion and wit, and completely without pity. His WWII veteran father’s head injuries may have been contributed to his cold and abusive behavior, and what eventually drove his mother to leave. Sergeant recalls these stories with a just-the-facts style that serves them—and the reader—perfectly. “I’ve painted a true picture of what it was like, but I hope I don’t come across as, ‘Oh, poor me,’ because it wasn’t poor me. It was just what everyone had to go through. It was no big deal. You just get used to it. You get used to whatever you’re used to, don’t you? That’s your existence and that’s it.”

Once Sergeant fully embraces his love of music, we follow him into the grimy, tiny clubs of the late-70s punk and post-punk wonderland, and though we can all but taste the stench, we feel free to embrace hope. His journey is filled with colorful characters, many of them you’ll recognize—Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Holly Johnson, Joy Division, OMD—all part of his ultimate journey to becoming a member of one of the most seminal bands of its era.

When asked about the early days of the band before fame he says: “Fame? I’ve got more fame from writing the book than anything else. More people pull me up in the streets and they’ll say, ‘I read your book. It’s great,’ and all that than, ‘I liked your guitar bit in that song,’ or whatever.’”

“It has been an amazing life,” Sergeant tells me, though Bunnyman is just the beginning of the tale. “I’m new to this world, the writing game,” he says, modestly. “I don’t know what the hell I’m doing, really.” And then he adds: “It’s just fun.”

When we speak, he’s visiting a friend in California, having a hell of a time. “I’m one of them blokes that likes to be outside and looking at things through my binoculars. Been watching the eagles,” he says, the metaphor not escaping me. “I have really nice binoculars.”

SPIN: You didn’t have it easy during those early days.

Will Sergeant: Yes, it was not a big deal. There were loads of families up our street that were like that. It was a time when the man ruled the roost and nobody would care if they were beating the wives or whatever, that sort of thing. It was ridiculous. That’s the only time when it came up. When you think about it, it wasn’t that long after the Victorian Era. Then you had the First World War and then the Second World War. It was just chaos. People’s brains must have been fried, but they didn’t know how to express it. Sure, my dad probably had some sort of disorder or not diagnosed and not even heard about, some sort of spectrum thing.

It was just different times, wasn’t it?

You’re very, very detailed at times.

Everyone is like, “How do you remember all that stuff?” It’s like, “I’ve remembered everything. I’ve remembered the things that I’ve remembered.” Do you know what I mean? When you put them all in a line, it looks like you remembered everything. I do remember being on the little path there, the pads, and having a picnic with my sister. We had a bottle of water and some jam butties, something like that. Probably about three or something, three or four. Things like that stick in your head, don’t they? I bet you can remember things when you were a little girl.

I went back to them places. I went back up the pads and I knew exactly where. I could remember what it was like. It was a sandy path and I remember going up there. There’s a hoar thorn hedge and it’s still there. Nothing’s changed. It’s exactly the same. You can see Liverpool across the fields. I remember walking to school that day when I had sandals on. We had to walk to school in the snow. We were just too scared to go home. We didn’t really know what to do. The school was only about a mile away, so it wasn’t too bad for us in thick snow with sandals on and wet socks. [chuckles] It was fun. At the time, it was fun.

You really embrace the “show don’t tell” writer credo. With your description of the club. Eric’s particularly, because when you talk about it, you can smell it through the pages.

Oh, yes. It stank. After you’d been in there a couple of hours or half an hour, you get used to it and it’s not in the forefront of your mind. It wasn’t even that was a thing. I’m just saying what it was like. Nobody used to go, “Oh, it stinks in here.” Nobody cared. It was our place. It was our little domain and our place and where we belonged. There was nowhere else where we belonged. There was a couple of other punk clubs. There was one called The Swinging Apple, but that one, to me, that came later. That came after punk was finished, really, and it was a bit shit.

It was all the divvy punks used to go there, the ones that came after the Pistols and the Damned and Wire and all that. We went there once and we thought it was crap. It was full of all the divs.

What do you think was so special about the post-punk movement and all those great bands that came out of it?

Punk had changed everything. It was like a year zero situation that was like a full-stop. Then, really, when you think about it, a lot of them bands that came after, they were not like them…like progressive rock. I don’t know, everyone had a different attitude. Big, long solos were out. It was a more concise thing, really. Some of the sounds and the elements of the sounds could harken back to the ’60s and the ’70s. I don’t know, it just developed naturally. Nobody was thinking about it. Nobody was going, “Oh, where are we going to go to next? We’ve just had punk.” It didn’t work like that. Things just naturally grow and develop. You can’t force them sorts of things, so it was just what happened. It wasn’t a preconceived plan or idea.

There was things in your mind where you knew what you couldn’t do. You couldn’t have a 10-minute drum solo, so that was just not in the palette of sounds that you could have. After the punk thing, you become aware of things without even realizing you’re aware of them. Plus, it just guided you. It was like a guidebook.

There was a guidebook, but then, who established the guidebook?

Just the kids. The kids that established the bands. It wasn’t built by the record labels and all that stuff. It was kids that were fed up and didn’t want to be into the progressive rock stuff of the ’70s or whatever. I used to love that stuff. I was into that when I was 14. I was barely getting into music in a serious way. It created an escape for me in my house. I loved my music and I loved the bands. Some of them, you play them now and you think, “God, what the hell was I thinking?” [chuckles] Some of them are still great. I even like Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and things like that because it’s a nostalgic thing. It takes you back to being 13 in your bedroom, playing it on a damn set record player or whatever.

I loved doing the book, it was like time traveling. It was real weird time travel situation you could visualize. I can visualize my bedroom, the starkness of it, and a few scabby blankets on my bed, and no carpet, and water on the windows. I remember there used to be pools of water on the window ledges because the condensation, because it was so cold. It used to freeze in the winter, you’d have these blocks of ice on the windows on the inside. [chuckles] I don’t remember being cold in bed.

I think you get used to the cold there.

It sounds like you look back on those days really nostalgically.

Yes, it was a great time. It’s like everybody. I’m no different to everybody else. It’s like, when you’re a kid, eyes are getting opened by all the stuff all the time. Sometimes, it’s getting opened by crap stuff, but other times, it’s getting opened by interesting stuff that really means something inside and takes you forward and gives you knowledge that’s valuable later on. I used to watch– We only had two channels. We had three eventually. We had BBC 1, BBC 2, and ITV. BBC 2 was the new radical channel, so they’d play quite weird films and stuff. I was always left on my own, so I could watch these films from being a very young kid.

You don’t gloss over a lot of things.

No. There was loads of strikes in England. At one point, the electricity used to go off a couple of days a week. There was power cuts and there was a lot of industrial strife going on between the miners and the politicians, and all that. We were growing up through all that stuff, so certain days, certain nights there was no telly. No lights, everyone had candles. There was a bread shortage. I remember that. Everyone was making bread because the bakers were on strike. There was loads of industrial action going on, like strikes and walkouts and things like this.

By the Europeans, Britain was known as “The sick man of Europe,” because it was just so much stuff going on with the unions and that. That filtered down to the people, and we couldn’t get a loaf, and the bins weren’t getting collected at one point. There was mountains of bin bags in Liverpool, full of rats, and it was mental.

At one point, the gravediggers were on strike. There was nobody to bury the dead, so there were plans or thoughts for people to be given permission to go into graveyards and dig their own graves. All these bodies mounding up in the morgues. They were going to have to get rid of them somewhere, so they were just about to give permission to families to be able to go and dig a grave for the granny or whatever. Then, the deadlock was broken and the gravediggers came back to work. It’s like something medieval.

Did you plan out your story beforehand? What was your process?

I just started at the beginning. There was a bit of sorting out trying to get in an align. It’s like a diary, almost. It’s not that difficult when you’ve already got the story. It’s not like you’re writing a crime thriller and you’ve got to keep people turning the pages. All this stuff happened, do you know what I mean? The story’s already written, you’ve just got to put the words down so it flows and people find it interesting.

I enjoyed it. I’m enjoying doing the next one. There’s a lad in it, the next one, that’s like Yorkie. I spoke to Yorkie about this and I remember it. It’s dead funny because he was only a kid and we used to rehearse in his basement, his mum used to let us. His mum was Gladys. She was amazing. She was a real Liverpool scouse mum, screaming at us to, “end the fucking drums now,” [Chuckles] down the stairs. She was there.

He wasn’t like anybody else in Liverpool. He’d wear this weird World War I nurse’s cape and he had this weird haircut where it was all shaved around here and he had this dead black bit on the top, little side part thing. Then, he’d walk ‘round town and he had a big ceremonial sword on his belt, a real sword with a scabbard with ornate metalwork on the outside. I don’t know where he got it, some sort of cattle resort or something, and he used to walk around town like that, with a sword on himself. [Chuckles] And nobody called him up on it. It was just a fashion affectation thing. Then I was thinking, “Bloody hell, Yorkie. Why didn’t all the scallies in the Liverpool beat you up or whatever?” He said, “No,” and then it registered, “Wait a minute. He’s got a fucking sword.” You can’t go around with a sword now, could you? You’d be locked up straight away.

There is definitely going to be a second book?

Oh, yes, yes. I’m doing it now. I’m just going to go into more the beginnings of the Bunnymen and the first recordings and first time in Europe, first time going abroad, our first gigs in America. The developments of the sound and the individual characters that created it. Yes, I can remember loads of great little things that happened, interesting stuff.

Was there any part of writing this book that was hard for you? Hard to write?

Yes. There probably was a bit, because my dad’s dead and I’m slagging him off. Although, I think I’d temper that with saying that I think he was on the spectrum, or whatever, and it was so cold. That was a bit weird. I felt a bit rotten about that, but it’s what happened, so tough titties, you know what I mean? It’s what happened. My sister read it and she said that’s exactly what it was like, this weird vibe, a bad atmosphere. She used to get hit and my brother used to get hit. I never really got belted, not much. Maybe now and then, but not much. I don’t know why, they always thought I was the lucky one. I never used to get any grief off him so much. Or I did, but they just didn’t see it.

Do you feel like you were honest in the book? Was there anything you held back?

There’s a couple of stories that I should have put in, that were interesting, and now, I’m trying to weave them into the next one as a flashback or something. My dad and his brothers had this woodworking factory. It all sounds fancy and that, but it was just a couple of sheds. There was five brothers and none of them really got on. I think my dad got on with one or two of them, but most of them hated each other.

I used to go there in the summer holidays and play in the woodworking factory. There’d be forklift trucks flying around, and trains, and big stacks of wood. There was no health and safety or nothing like that. I would just be left to my own devices. I’d go and build fires or whatever, do those sorts of things. I’d have all the scrap work, make a fire somewhere. Dodgy stuff.

There was a fight going on between two of my uncles. I can’t remember which ones, but it was a proper fight. I was just watching it like a little kid. There was this tray of machine parts, it was some cogs and little bits, and they were all in this liquid that looked like diesel. They were just soaking it to get the rust off or whatever. One of my uncles grabbed this tray and threw it at the other uncle, they all had overalls on, and it all went all over him. Then he started throwing matches at him, to try and set him on fire. [chuckles] The matches were going out. The other thing is diesel, it’s not that flammable, really. If it had been petrol, he would have gone up like Hellraiser or whatever. The matches were actually going out. I remember because he was throwing them, they were going out before they were hitting him.

It was more a symbolic: “I hate you this much, I would set you on fire if I could.” Two brothers and I’m like seven years old watching it. Nobody was going, “Get away, Will,” or whatever. It was just uproar in the big shed.

I forgot to put that one in.

What do you hope readers take away from your story?

Just that they find it entertaining and interesting. Really, that’s it. It’s not Shakespeare. [chuckles] It’s not meant to be some map for how to live your life or whatever. It’s just a story, isn’t it? It’s just my memoir and that’s it. I just really liked doing it, and I’m going to more. I think my biggest asset is, and this counts for guitar, and on painting, and all the rest of it, is, I’ve got this weird, artistic imagination. I think it’s the only thing that I have got, is an imagination. Everything else comes after that. You know what I mean?

That’s probably down to me being left on my own, and having to make my own fun.

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/03/03/765/n/1922564/0b94541a69a718b304a9e1.72082455_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/02/25/940/n/1922564/9f3e52c1699f6af941f710.31293332_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/02/18/893/n/1922564/857ece5a69962087501ab8.98904531_.jpg)