Dave Stewart still vividly recalls the day he found out Eurythmics went to No. 1 in the U.S. with their 1983 single “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This).” He and Annie Lennox were in a hotel room in San Francisco, preparing to play a show, and received a phone call from their record label rep sharing the good news.

“[The label] said, ‘Oh, we’ve got something to tell you—you’re number one,’” Stewart tells SPIN, Zooming in from the Queen Mary II somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean on his way to England.

“We hung up, and we didn’t know what to do. We looked out the window; everything looked the same. So we both started jumping around on the bed like kids, and going, ‘We’re No. 1!’ And then we were going, ‘Oh, I wonder what that means.’ We soon found out—that night we were playing [a show], and it was just queues and queues in the street and outside and everywhere. And we were like, ‘Holy shit.’”

As it turns out, he and Lennox had a similarly delighted reaction when news broke that Eurythmics were being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this year. They texted each other and then hopped on the phone to soak up the news together.

“My wife [and] my kids go, ‘Dad, you’re terrible to give birthday presents to,’” Stewart says. “It’s ingrained into British culture, I think, to be, ‘Oh, thank you very much,’ and be totally shy about it, you know? But between the two of us, we weren’t shy at all. We were going, ‘Ha ha! Woo hoo!’”

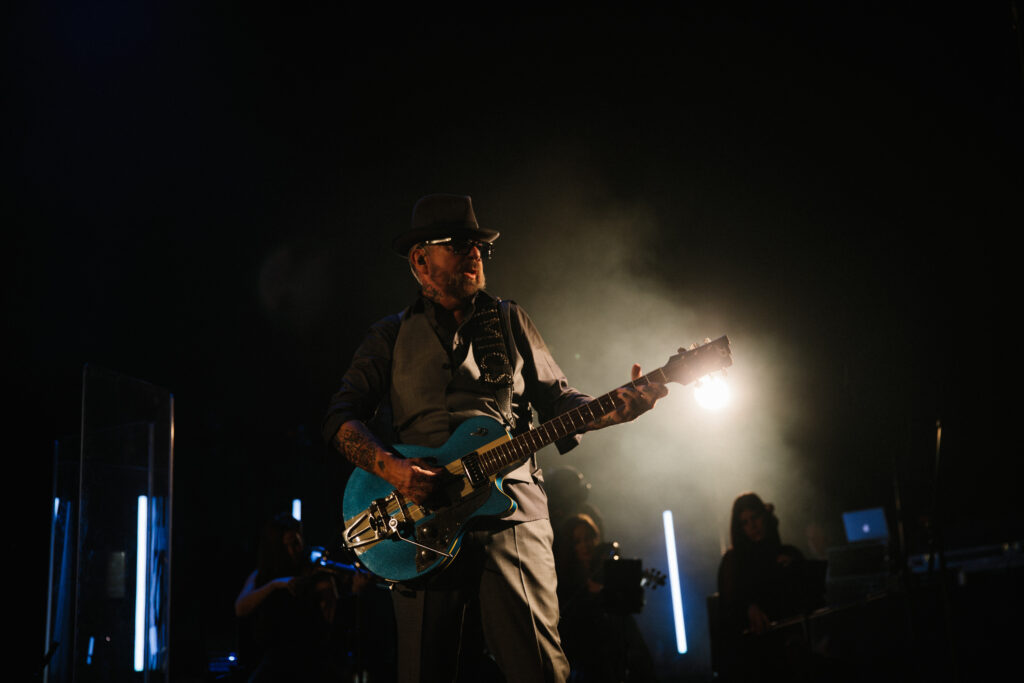

(Credit: Fryderyk Gabowicz/picture alliance via Getty Images)

(Credit: Fryderyk Gabowicz/picture alliance via Getty Images)

That’s not the only major honor Stewart and Lennox received this year: They were also inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, an acknowledgment of the music they’re written both together and separately across decades-long careers. A few weeks ago, Stewart released a typically ambitious solo album, Ebony McQueen, based around childhood memories that were jogged loose when he met a woman by that name.

Stewart has an uncanny ability to see connections between music genres; accordingly, he’s collaborated with a jaw-dropping number of artists throughout his career; to name just a few, Aretha Franklin, Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, Stevie Nicks, and Mick Jagger. Ebony McQueen certainly reflects his understanding of the ways blues music weaves through so many different eras and styles of music throughout history—”why it’s all joined together in India to Africa to the coal mines, and the North of bearing the bitter cold, Irish music, Scottish music.”

However, Ebony McQueen also boasts “influence from my father playing Rodgers and Hammerstein every morning through to me hearing the blues to the Beatles to the Kinks to Pink Floyd,” Stewart says. In practice, that equates to a lush, theatrical album that would appeal to fans of Jellyfish and XTC; its songs touch on power pop, orchestral rock and the ’60s British Invasion rock.

Stewart says he’s not sure yet what the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony will look like for him and Lennox. “I don’t know what we’re going to do yet or how long we’re allowed to play for, or which way we’ll set up,” he says. “We can play any way. We’ve done arenas with just me on acoustic guitar and Annie singing, or we’ve played with orchestras or we’ve played with just a small band, a seven-piece band, a five-piece band. There’s many ways in which we can perform.” In the meantime, Stewart is also working with collaborators to turn Ebony McQueen into a movie script.

SPIN: How did the story and project of the new record came together? What was your kernel of inspiration?

Dave Stewart: [Stewart describes being on a tiny island and encountering a woman while out and about.] She was telling me her name, but she said, “I prefer my maiden name.” I said, “What’s that?” She said, “Ebony McQueen.”

I was riding on my bicycle towards my place, and I sang the whole chorus in my head. And I thought, “Ah, this is a very infectious melody and song.” I sang the words as well: [sings] “Ebony McQueen, I think I met her once inside a time machine.” I was just goofing about. But then I started to make a whole character out of Ebony McQueen as a voodoo blues queen.

[And then] I went back to when I first discovered music. [At first] I wanted to play soccer for Sunderland. It wasn’t until my knee was shattered in several places—I was stuck at home, and my mother had left my dad [at] literally the same time and moved to London. They separated. My dad was depressed and gone to work. My brother was away at college. So I was at home in the house with a leg that couldn’t walk properly. I was so down.

(Credit: Courtesy of Bay Street Records)

(Credit: Courtesy of Bay Street Records)

I decided to put on a vinyl record, which I never did. It was sent from Memphis by my cousin. And it said: Robert Johnson, King of the Delta Blues Singers. I was like, “My God, what the hell is this?” It sounded like something from outer space. It was just so surreal in the Northeast of England, hearing “Hell Hound on My Trail” and [a] strange wailing voice from a hotel room in the South. I went into a trance.

Then this whole thing started to come flooding out. It was a story that I’ve blocked for ages about my teenage slice of my life, about my mom and my dad.

That’s always incredible when you find and unlock something deeply held. It’s timing too—maybe 20, 25 years ago, you wouldn’t have had language to write about it.

After I came out of the trance from that record—I hid that record under my bed. [Laughs.] Because I thought it was like some weird, special thing. And then I put on the radio. This was 1966. Suddenly, I was bombarded with the Kinks, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Small Faces. Everything blew my mind, literally in the kitchen, listening to this on my own. I realized they were all singing some weird blues thing in a different way.

My brother had a guitar I started to work out something on one string, two strings, little bits of blues, like [sings a riff] That’s all I could really play. And then I started to pick out melodies, and then I just wouldn’t put it down.

It was like Excalibur. It was like, nine hours a day, and I’m trying to work out all the songs I ever heard coming on the radio. But I didn’t know how to tune it! So I was learning them all with a weird tuning.

[I also visited] a man two doors down [from me] Mr. Len Gibson, from Sunderland. All his friends were tortured to death. And he made a guitar out of bits of wire and wood that he’d found to cheer up the surviving guys. I didn’t realize he tuned his guitar to something different too, more like a banjo. But he was very helpful in showing me how to play rhythms and things like that.

What’s been the most challenging and rewarding thing adapting the music and the stories and the themes in there to the movie script?

Well, fortunately, I went to see a chap in the Northeast of England who was the head of Northern Theatre. [I said] here’s my story, would you like to write the script with me? Because he would understand the North and also he knows all of the actors and actresses in the Northeast. He loved the story, and he agreed. So we’ve met all over the place, all over the world—on a tiny island, in America, in London, in the Northeast. And we hammered out a draft and then this lady called Selma Dimitrijevic, she joined in.

Between Norm and her, they’re on the third draft. [It] sticks to a coming-of-age story where a teenager, based on myself and my stories, discovers not an escape, but a way to alleviate the situation through music. And eventually, through music, [the teenager] starts to meet his own tribe.

(Credit: Courtesy of Bay Street Records)

(Credit: Courtesy of Bay Street Records)

Over time, you’ve realized and understand how these different musical threads tied to the blues came together, across eras, genres and places. As a creative, there’s something so exciting when you have those connections.

Oh, yeah, I mean, I’m sure you, as a writer, when you write something for yourself, and you realize, “This [has a] fairly similar feeling to something by George Orwell or Ray Bradbury,” or Dickens or whoever. You hadn’t imagined it to be connected with [them], but you’re writing about a dystopian future, or whatever you’re writing. Sometimes it’s mind-boggling. For me sometimes I read something from 1000 years ago and it’s a Greek philosopher talking about teenagers and you go, “Fucking hell, okay, now, he’s describing exactly teenagers now.”

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/19/981/n/1922564/93076eb0682bb18c994e06.89379902_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/23/715/n/1922564/1e63d6e168309df259d956.72331408_.png)