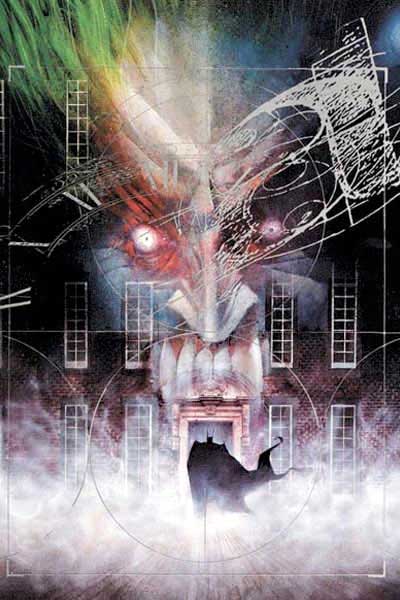

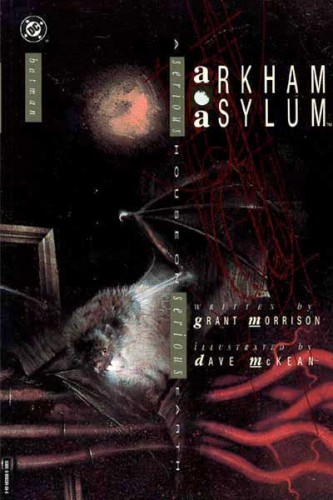

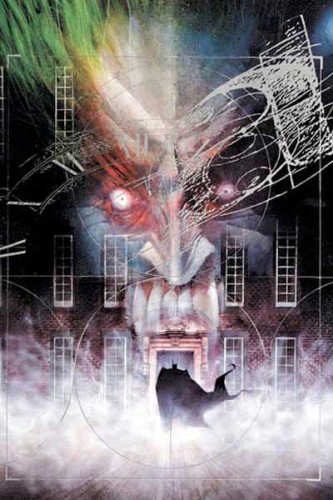

Since his creation, the Batman has undergone a variety of radical reassessments. From the camp parody version of the sixties, to the dark vigilante of the seventies, to the big-budgeted merchandising exercises of the nineties, finally to arrive in this new century with a film adaptation that seems to please both Batman fans and mainstream audiences alike. But the character was taken to new extremes by innovative Scottish writer Grant Morrison with the 1989 release of Arkham Asylum, illustrated by Dave McKean and prophetically subtitled A Serious House On Serious Earth.

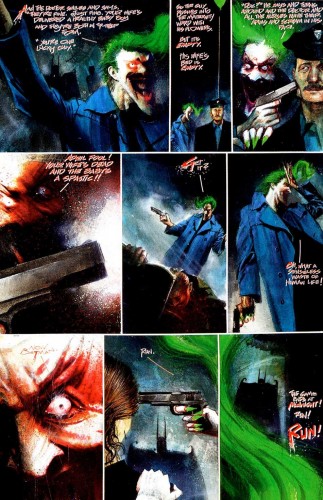

It’s the 1st of April, in a Gotham free of continuity squabbles, the inmates of Arkham Asylum have taken the staff hostage and issue their demand: The Batman, alone. On this memorable night, the abominable history of Arkham unfolds and Batman faces old adversaries: The Joker, Two-Face, Killer Croc, and others. He also encounters suppressed and unwelcome doubts concerning his own sexuality. Grant Morrison didn’t want to do the realistic Batman. His idea was to do a Batman which was a purely symbolic figure, which wasn’t a man at all. Dave McKean described him as a totemic animal/man, a type of mythological creature as opposed to the Frank Miller and Alan Moore realistic superhero. Many writer/artist teams lack the collaborative approach. Often the final script is sent to the artist for illustration with no discussion in between. The McKean/Morrison partnership, however, proved to be inspired, as their discourses provided the spark to enhance the final script.

It’s the 1st of April, in a Gotham free of continuity squabbles, the inmates of Arkham Asylum have taken the staff hostage and issue their demand: The Batman, alone. On this memorable night, the abominable history of Arkham unfolds and Batman faces old adversaries: The Joker, Two-Face, Killer Croc, and others. He also encounters suppressed and unwelcome doubts concerning his own sexuality. Grant Morrison didn’t want to do the realistic Batman. His idea was to do a Batman which was a purely symbolic figure, which wasn’t a man at all. Dave McKean described him as a totemic animal/man, a type of mythological creature as opposed to the Frank Miller and Alan Moore realistic superhero. Many writer/artist teams lack the collaborative approach. Often the final script is sent to the artist for illustration with no discussion in between. The McKean/Morrison partnership, however, proved to be inspired, as their discourses provided the spark to enhance the final script.

To start with, Grant didn’t know who was going to be illustrating the book. Berni Wrightson and Bill Sienkiewicz were approached but, due to other commitments, had to turn it down. However, it turned out for the best when Dave McKean got the job. Dave said, “Why bother making it realistic? Let’s make it fuzzy, then you don’t have to pretend that it’s real.” This completely changed the way Grant thought about tackling the final draft. Three years had elapsed since the initial synopsis and proposal were sent to DC Comics. One of the main sticking points was Grant’s uncompromising attitude toward his subject matter. After delivering his 64-page script, DC said “We really like this, but…” and proceeded to suggest changes. Because of this, Grant didn’t want to do it. “What’s the point of an adult comic if we can’t touch on these elements?” Once there was some discussion, Grant got to keep everything.

To start with, Grant didn’t know who was going to be illustrating the book. Berni Wrightson and Bill Sienkiewicz were approached but, due to other commitments, had to turn it down. However, it turned out for the best when Dave McKean got the job. Dave said, “Why bother making it realistic? Let’s make it fuzzy, then you don’t have to pretend that it’s real.” This completely changed the way Grant thought about tackling the final draft. Three years had elapsed since the initial synopsis and proposal were sent to DC Comics. One of the main sticking points was Grant’s uncompromising attitude toward his subject matter. After delivering his 64-page script, DC said “We really like this, but…” and proceeded to suggest changes. Because of this, Grant didn’t want to do it. “What’s the point of an adult comic if we can’t touch on these elements?” Once there was some discussion, Grant got to keep everything.

Or so he thought. Unfortunately Warner Brothers bought DC and were concerned about Grant’s treatment of the character. After the expanded 120-page script had been written, Warner Brothers stepped in. The Tim Burton film was coming out and they were worried that Grant’s version of the Batman would contradict theirs. Warners wanted a PG-rated Batman because they didn’t want to jeopardise the fifty million dollars they had sunk into the movie. Because of this a few things were removed or changed. For instance, the Joker was originally to be dressed as pop singer Madonna. Warners didn’t want that because they seriously thought readers would think Jack Nicholson was a transvestite. Is this the conclusion you would jump to?

Doctor Amadeus Arkham is a brilliant yet predictably disturbed psychiatrist who, in the twenties, brings his work home with him, and converts his house into an asylum. In the middle of the book there is a cannibal scene where Amadeus eats bits of his own family. Grant was not allowed to have cannibalism in a Batman book, so Dave simply removed all the captions which described what was going on, making the scene quite abstract indeed. The elevation of comics to a literary medium was no doubt assisted by DC’s decision to censor certain verbs from the text. The word ‘masturbate’ was removed. It was originally in Doctor Arkham’s report which was a very straightforward medical report, cold and clinical. The word ‘f*ck’ also came out, which was in the scene where the Joker pinches Batman. The original line ‘Take your f*cking hands off me’ was changed to ‘Take your filthy hands off me’ because Batman never swears. He has a strict boy-scout upbringing. Grant didn’t mind that so much, as he’d only put it in there for shock value anyway.

Doctor Amadeus Arkham is a brilliant yet predictably disturbed psychiatrist who, in the twenties, brings his work home with him, and converts his house into an asylum. In the middle of the book there is a cannibal scene where Amadeus eats bits of his own family. Grant was not allowed to have cannibalism in a Batman book, so Dave simply removed all the captions which described what was going on, making the scene quite abstract indeed. The elevation of comics to a literary medium was no doubt assisted by DC’s decision to censor certain verbs from the text. The word ‘masturbate’ was removed. It was originally in Doctor Arkham’s report which was a very straightforward medical report, cold and clinical. The word ‘f*ck’ also came out, which was in the scene where the Joker pinches Batman. The original line ‘Take your f*cking hands off me’ was changed to ‘Take your filthy hands off me’ because Batman never swears. He has a strict boy-scout upbringing. Grant didn’t mind that so much, as he’d only put it in there for shock value anyway.

Grant’s Batman is a far cry from the fearless character familiar to news-stands worldwide. He planned the book as a psychodrama in which the house becomes a human head where all the characters become personifications of human fears and obsessions. The Batman is made an anal compulsive character – if he was afraid of anything, it would be sex. Sex is his big terror and that’s the area the Joker starts probing when Batman arrives. The casual reader is in for a shock. Arkham Asylum looks like a Batman book and has a conventionally simple storyline, but it is submerged in complexities and many of its ideas are shrouded. The scenes in which Doctor Arkham visits Aleister Crowley and Carl Jung are really there to tell us to go off and read a couple of their books, which would allow the story to open up in another way.

Grant’s Batman is a far cry from the fearless character familiar to news-stands worldwide. He planned the book as a psychodrama in which the house becomes a human head where all the characters become personifications of human fears and obsessions. The Batman is made an anal compulsive character – if he was afraid of anything, it would be sex. Sex is his big terror and that’s the area the Joker starts probing when Batman arrives. The casual reader is in for a shock. Arkham Asylum looks like a Batman book and has a conventionally simple storyline, but it is submerged in complexities and many of its ideas are shrouded. The scenes in which Doctor Arkham visits Aleister Crowley and Carl Jung are really there to tell us to go off and read a couple of their books, which would allow the story to open up in another way.

For some, this may appear to be out-of-place in a superhero book. One reason for such highbrow content is that it didn’t initially start as a Batman project. When Grant approached DC he wanted to do a graphic novel about Arkham Asylum and about its characters and inmates. Batman didn’t figure much in it. It wasn’t until Grant started writing that Batman suddenly appeared, and the author had to do something about him. “The attraction of Batman and the Joker and all these characters is the way the reader brings preconceived notions to them. Part of the fun is turning these notions upside down,” Grant said. “Most readers don’t expect Batman to push glass through his own hand. If these were new characters, those actions could be easily grasped and then the reader would lose the charge that the author has done something different.”

For some, this may appear to be out-of-place in a superhero book. One reason for such highbrow content is that it didn’t initially start as a Batman project. When Grant approached DC he wanted to do a graphic novel about Arkham Asylum and about its characters and inmates. Batman didn’t figure much in it. It wasn’t until Grant started writing that Batman suddenly appeared, and the author had to do something about him. “The attraction of Batman and the Joker and all these characters is the way the reader brings preconceived notions to them. Part of the fun is turning these notions upside down,” Grant said. “Most readers don’t expect Batman to push glass through his own hand. If these were new characters, those actions could be easily grasped and then the reader would lose the charge that the author has done something different.”

The Tim Burton Batman (1989) movie made the Caped Crusader headline news for six months, during which time editions of Moore’s The Killing Joke and Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns were in constant demand. Arkham Asylum caught the tail-end of that particular bandwagon. Most of the 200,000 people who bought that first edition of Arkham Asylum were probably kicking themselves, saying “What’s this peculiar thing I’ve bought?” But that’s their problem. Many readers were probably expecting Grant Morrison to rehash The Dark Knight, but what’s the point in doing that? The comic fan’s demand for background information have often led to stories weighed-down by exposition. Continuity is the bane of comics. “It would be okay if it was continuity between six brilliant minds, but not continuity between one guy who can write quite well and a bunch of tossers who couldn’t grab a pen between their teeth!” That, for Grant Morrison, was the problem with DC comics. “Unfortunately, the guys writing the rules are complete idiots. Why should you abide by an idiot’s rules? It’s just pulling down your imagination and your ideas and this annoys me. That’s why I try to sidestep continuity and mess it up as much as possible.”

The Tim Burton Batman (1989) movie made the Caped Crusader headline news for six months, during which time editions of Moore’s The Killing Joke and Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns were in constant demand. Arkham Asylum caught the tail-end of that particular bandwagon. Most of the 200,000 people who bought that first edition of Arkham Asylum were probably kicking themselves, saying “What’s this peculiar thing I’ve bought?” But that’s their problem. Many readers were probably expecting Grant Morrison to rehash The Dark Knight, but what’s the point in doing that? The comic fan’s demand for background information have often led to stories weighed-down by exposition. Continuity is the bane of comics. “It would be okay if it was continuity between six brilliant minds, but not continuity between one guy who can write quite well and a bunch of tossers who couldn’t grab a pen between their teeth!” That, for Grant Morrison, was the problem with DC comics. “Unfortunately, the guys writing the rules are complete idiots. Why should you abide by an idiot’s rules? It’s just pulling down your imagination and your ideas and this annoys me. That’s why I try to sidestep continuity and mess it up as much as possible.”

As the approaches to Batman become more literary, the character continues to thrive in the visual media: Comics, television, cinema, boxer shorts, etc. Yet one wonders whether a successful attempt could be made to transfer the character into prose. Me? I’ll just wait for the pop-up book. And it’s on that note I’ll wrap-up this week’s review, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another bargain-basement barker for…Horror News! Toodles!

As the approaches to Batman become more literary, the character continues to thrive in the visual media: Comics, television, cinema, boxer shorts, etc. Yet one wonders whether a successful attempt could be made to transfer the character into prose. Me? I’ll just wait for the pop-up book. And it’s on that note I’ll wrap-up this week’s review, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another bargain-basement barker for…Horror News! Toodles!

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/02/02/039/n/1922564/64cfff5c698139b8e3a320.43487307_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/02/12/809/n/1922564/0bad645867ace78c3a1764.72612350_.png)