Farrah Penn: Hi Celeste! This is Farrah with BuzzFeed. Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me today. I’m so thrilled to talk about this book. How are you doing?

Celeste Ng: I’m doing well, thank you! How are you?

FP: I’m great! Not looking forward to another Los Angeles heat wave over here, but otherwise, can’t complain!

CN: It’s just starting to feel like fall over here in Boston, as of today.

FP: That sounds so lovely. I’ve enjoyed Boston the few times I’ve visited!

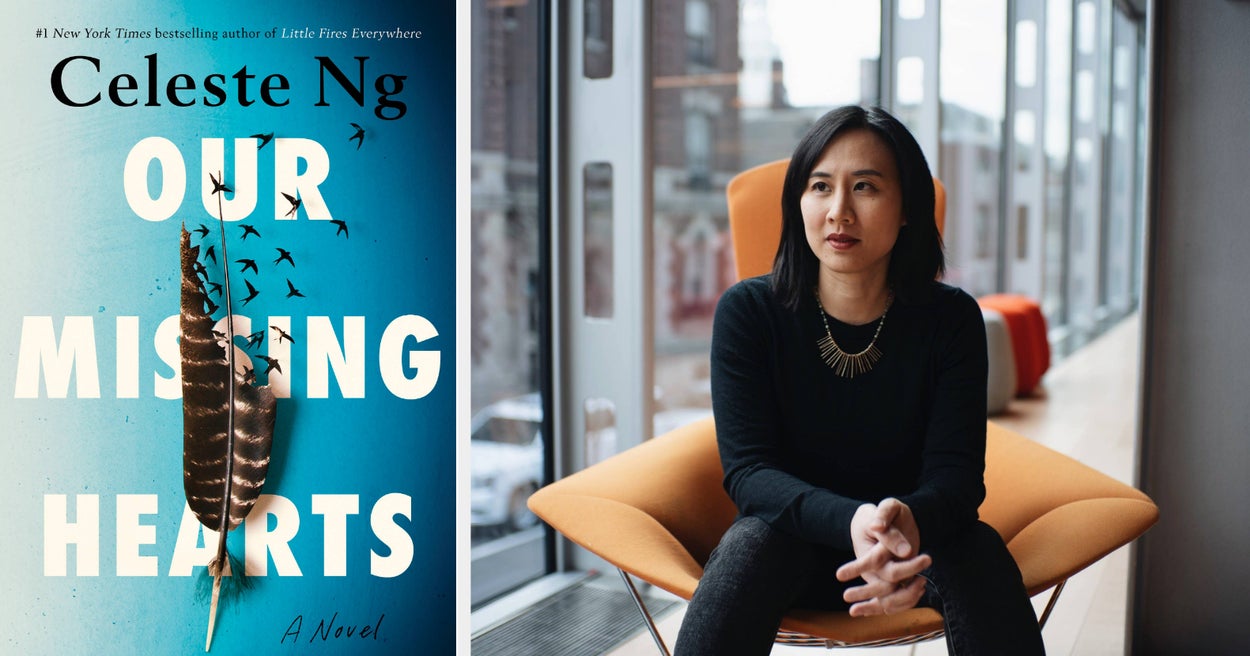

Our Missing Hearts is coming out soon, and I’m excited to talk to you about this novel. This book has been categorized as dystopian, which is a bit of a departure from your previous books, but at the same time, its themes so closely align with the current climate. In your author’s note, you said it best: “Bird and Margaret’s world isn’t exactly our world, but it isn’t NOT ours either.” What made you want to write this story, and why now?

CN: I came up with the first seeds of this story right after finishing my second novel, Little Fires Everywhere. At that time, it was a mother-son story set in a fairly realistic world about a creative mother, and her son who didn’t understand her work, and maybe even saw it as a rival to him.

This was in October 2016 — so while the idea was still forming in my mind, the 2016 election happened, along with everything that it emboldened: the rise of the far right, increased nationalism and xenophobia. … All of that started to bleed into the story — they felt related to the questions I was asking about this family. Immersed in a world that felt like it was becoming a dystopia, I couldn’t write a book that pretended those elements didn’t exist. So, I started working them into the world of the book. Turning up the volume on our own world, so to speak.

It was a way of exploring the world we were in, and the issues I was struggling with in my own life. Such as: How are you supposed to raise a child in a world that feels like it is totally falling apart? How do you maintain hope in the face of all this?

FP: Oof, yes. Those are huge questions to explore. And it’s so interesting to hear that the seeds of this idea arrived way back in 2016. But speaking of raising a child in this tumultuous time, this is also a story that centers around motherhood — the decisions Margaret makes for Bird, but also for the greater good. Why was this important for you to explore?

CN: Partly, it’s personal: I’m a mother myself, so how to raise a child — and how to make the world into a place I’d want them to live in! — is very much on my mind.

But the past few years have also led me to think a lot about what it means to be part of a community, what it means to be a responsible member of society, what we owe to each other, so to speak. As a parent, I’m trying to get my kid to think about those kinds of issues, and it’s made me articulate what it is that I believe about them. So, I guess my own preoccupations have a way of working their way into my fiction!

FP: Yes, absolutely. It’s so important to continue these ongoing dialogues and discussions. And to segue into my next question, your book does follow two 12-year-old children. Sadie, a young girl who’s been removed from her home and re-placed because her parents protested PACT (The Preserving American Culture and Traditions Act), is a fictional character in this story, but she represents a real history of displacing children in the US and beyond. What made you want to navigate this subject in particular?

CN: I think most of us would like to believe that we’d live by our principles and stand up for what we believe is right — but that calculation becomes really complicated if your children might be at risk. Even before the Trump years, I had been thinking that the worst thing I could imagine, as a parent, was being separated from my child. There’s a long history of this, of course, both in the US and elsewhere — from the separations of enslaved families to the residential schools for Native American children to the foster care system — and those had always been terrifying to me.

And, of course, when Trump’s policy of separating migrant families at the border began getting attention, I think it was a wakeup call to many that this wasn’t just something that happened in the past, it is something that still happens, and that could happen to anyone, if those in power decide to make it so.

Because the novel was shaping itself around a mother and a son, the space between them, and the son’s search to find his mother again, PACT and the policy of taking children from their parents as political control made perfect sense in this world.

FP: It is a heartbreaking and terrifying reality. As I was reading I kept thinking, “Wow, this world feels so extreme,” but would then go on to draw parallels to our own world. And speaking of those parallels, did the rise in banned books in the last few years influence your creation of this story?

CN: It did! Book bannings have been in the news a lot in the past few months, but there’s really been a steady rise in it over the past few years, as you mention. So, it wasn’t at all hard to imagine that escalating, as it seems to be now.

On top of that, I was following the gradual crackdown on democracy that’s happening in Hong Kong — my family is from Hong Kong, so it’s of personal interest to me. I would read stories about the Chinese-controlled Hong Kong government censoring pro-democracy books, and banning pro-democracy protests and signs. Sometimes, it becomes almost farcical: At a certain point, protestors started holding up blank pieces of paper, because there were so few things they were allowed to put on signs — and then, the authorities banned blank paper.

So, I was really struck by watching democracy unravel in real time in multiple places around the world, and one of the common first steps seemed to be in limiting what people were allowed to say.

FP: This is, once again, a heartbreaking reality. Our Missing Hearts also explores anti-Asian hate and discrimination, which we have unfortunately seen a rise in within the US. What do you hope people take away from this book?

CN: I always write not because I have an answer, but because I have questions. So, I hope the book makes people aware of anti-Asian hate and anti-Asian violence, if they didn’t know about it already — but I especially hope people will ask themselves what they will do about it. It’s easy to be a bystander, or to feel like someone else’s problem isn’t your own, because it doesn’t directly affect you. However, the truth is that these problems are societal, and they affect all of us. For me, the book raises questions about how we connect with other people, how we form a community, how we maintain empathy for other human beings. Those are all the questions I hope readers will sit with, after turning the last page.

FP: You do a wonderful job showing empathy and connection in this book. Stylistically, Our Missing Hearts is different from your previous ones (there are no dialogue quotes, for example). I was hoping you could talk a little bit about that decision?

CN: Oh, I’m so glad you asked this! (Word nerd hat on.)

When I started writing the novel, I found that I was instinctively writing without quotation marks. I felt that was right, but I had to think about why. (I’ll be honest, I usually hate when there are no quotation marks.)

This is how writing goes for me, a lot of the time: My instincts will lead me a certain way, and it takes a minute for my rational brain to figure out whether that instinct is right, and most importantly, why.

I wanted the novel to feel slightly folkloric, almost dreamlike; for Bird, the events feel a little bit like stepping into a fairytale, one of the stories his mother told him when he was young. When you think of a story being told out loud, the way folktales often are, the voice of the person telling it and the voices of the characters kind of merge, if that makes sense. There’s a blurring between the person narrating, and the words of the story, and the things the characters say. So, removing the quotation marks helped create that effect for the reader. Instead of a clear, formal, writerly quotation mark, neatly marking off what’s dialogue and what’s narration, it blends a little.

For a similar reason, I decided to use unnumbered chapters — numbered chapters felt very formal, like clear markers, that remind you you’re reading a book. Again, because I wanted the reader to have the feeling of a told story — where one part leads naturally into the next, and there are no hard divisions — those unnumbered sections felt like the right fit.

FP: This is all so fascinating. To me, your decision does make sense for this story — and it works!

CN: It’s always good when it feels like my instincts are right, rather than leading me astray!

I should add that the novel has a lot of storytelling, and particularly oral storytelling, in it — so, the idea of a story that is told aloud, vs. read, felt organic.

FP: Absolutely! Storytelling is such a central element to this book. The power that stories hold. Is this part of the reason why you decided to tell this story through the lens of a 12-year-old character?

CN: I really wanted to explore this world through the perspective of a child — but a child who was approaching adulthood — because to me, the novel is partly about widening your perspective on the world, about slowly becoming aware of the context you’re in.

When you’re a young child, your world is often very small, and it’s often around that age that you slowly become aware, “Oh, there’s all this history I didn’t know. There are all these places I’ve never been.” It’s like the frame around the picture of your life gets bigger. You start seeing your parents as people who have, and have always had, their own lives. And because of all that, your sense of who you are, and what your place in the world is, changes.

In some ways, the novel is a coming of age story — as Bird leaves home and ventures out into the world, his awareness of the world grows, too. As readers, we slowly become aware of what this world is like alongside him. So, he felt like the right guide, so to speak, for us to follow.

FP: Yes, this is so true. It’s very clear to me through this conversation, and through your author’s note, that a lot of research went into writing this novel. What was your research process like for you, and is it part of the process that you enjoy?

CN: The truth is that I’m intimidated by research — that’s partly why I write fiction, because then I can change things around as I see fit! But in this case, it felt really important to acknowledge that these things have happened and do happen, that I didn’t make them up out of whole cloth. I knew I wanted to write about the experience of anti-Asian violence, for example, but I didn’t want people to think this was a new thing that only arose because of COVID and Trump. There’s a long history of anti-Asian violence in the US, stretching back centuries, and yet, many people have never learned about it. I didn’t want to add to that erasure; I wanted to shine a light on it. Similarly, as we said above, there’s a long history of family separations, of removing civil liberties from groups that are seen as “other,” of racism toward many groups. Even though I was focusing on this one group — those of East Asian descent — I wanted to acknowledge that many, many other groups have experienced something similar.

For this book, research was partly looking at history — reading about times in the past when authoritarian governments came to power — but it was also reading the news, and paying attention to warning signs that similar things might be brewing now. Starting from 2016, when I started writing the novel, I kept a running file of news articles that felt like they spoke to the book, that were describing things that might happen in this world. At a certain point, I realized I was bookmarking articles that described things I’d already written coming true. History really does repeat itself if we don’t pay attention to it.

:quality(85):upscale()/2026/02/02/039/n/1922564/64cfff5c698139b8e3a320.43487307_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/02/12/809/n/1922564/0bad645867ace78c3a1764.72612350_.png)