This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Dragons pop up all over global folklore, in some shape or form. Some, like the Asian Lungs or Eastern European dragons, are very serpentine, with long bodies, sometimes with legs, sometimes without. Others are what most folks of Western European descent would recognize: horns, wings, at least two legs, a mouthful of sharp teeth perfect for biting through a questing knight’s armor. Today, we’re looking at some of the most beloved and famous dragons in mythology and literature.

Why do we love dragons so much?

With how prevalent dragons are, it’s not surprising that there’s been a couple theories created as to why this is.

There are two main schools of thought on the subject, outside of religious uses. There’s the thought that dragons were based on real creatures, and then the thought that dragons were based on encounters with fossils that were randomly encountered by past peoples. For what it’s worth, I think it’s somewhat of a blend of the two. I mean, there very rarely is a hard and fast rule for ANYTHING, much less when it applies to humans. We like to make things complicated whenever possible. For instance, we know that medieval monks often relied on the reports of far off animals and lands from traveling knights. Which means it often turned into a game of telephone, added on top of the struggle to explain this thing that is anything like what we know as a dragon.

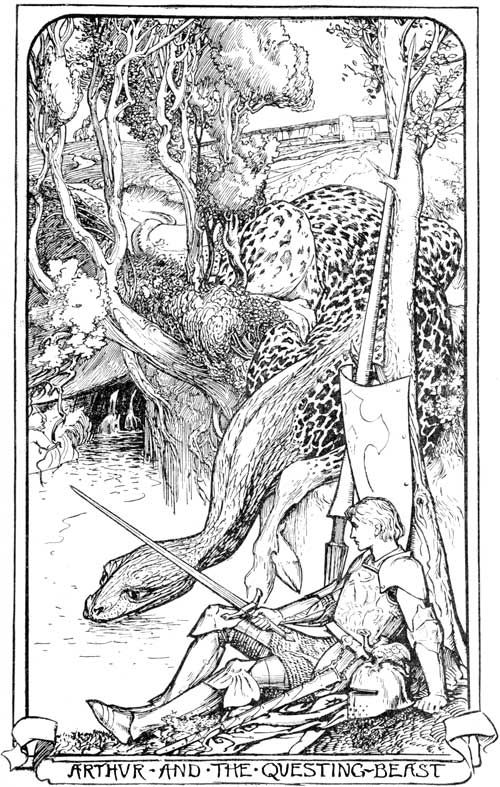

Take the Questing Beast, or Beast Glatisant, a monster of Arthurian legend: it had the head and neck of a snake, the body of a leopard, the haunches of a lion, and the feet of a hart. A beast of mythical lore, or just a giraffe with a little bit of extra razzle-dazzle added in?

Unusual Suspects Newsletter

Sign up to Unusual Suspects to receive news and recommendations for mystery/thriller readers.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use  Arthur and the Questing Beast, Henry Justice Ford (1904)

Arthur and the Questing Beast, Henry Justice Ford (1904)

We know that there are some cultures that likely based some of their folkloric creatures around fossils they came across. You can read more in Adrianne Mayor’s First Fossil Hunters and Fossil Legends of the First Americans (both books I highly recommend picking up if you’re interested in the subject, as they are meticulous in their research and incredibly fascinating), but long story short, the griffin of Scythian mythological origin is likely based off the bones of Proceratops encountered during nomadic travels. Stories of the Greek Cyclops likely came from encounters with Pleistocene dwarf elephant skulls. These elephants lived in coastal caves on islands in the Aegean Sea. You know, like Polyphemus. Needless to say, the situation with dragons is probably a little Column A, a little Column B. Humans are natural storytellers and can’t help but tell stories about the world around us, no matter what era we’re in. No matter where we are in this pale blue dot we call home. These 12 dragons, some of the most famous dragons in mythology, prove it.

(Side note: If you’re ever feeling down, I highly recommend you look up a picture of Guericke’s Unicorn. You will giggle.)

The Most Famous Dragons in Mythology and Literature

1. Fáfnir

Depiction of Sigurd and Fafnir from the right portal plank outside the Hylestad Stave Church in Norway. The carving dates back to the 12th century.

Depiction of Sigurd and Fafnir from the right portal plank outside the Hylestad Stave Church in Norway. The carving dates back to the 12th century.

Fáfnir comes the Nordic legends of the Volsunga Saga, and he wasn’t always a dragon. His original form was never explicitly described, but it’s often assumed that he was likely a dwarf as that’s what his brother Regin was described as. Although you can’t always assume that the brother of a dwarf will also be a dwarf. (Isn’t Norse mythology fun?) However, as a dragon, he’s initially described as a wyrm, or a giant scaled creature without arms and legs. Later iterations, as influences from Germanic tribes came along, he gets some shoulders, suggesting some legs to go with them. The very simplified story goes that Fáfnir’s father was given some cursed gold by the gods after they accidentally killed one of Fáfnir’s brothers. Fáfnir and his living brothers ask their father for some of the gold but their father refuses, leading Fáfnir to kill his father out of greed and flee with the gold out into the wilderness. Years pass and Fáfnir is turned into a dragon by his lust for gold. He is later slain by Sigurd, one of the heroes of the Volsung Saga, after Sigurd is taught how by Regin.

Now, if you’re interested in reading more of the saga, if only to get more than the very shortened version that I wrote out, I highly recommend reading the saga. There are a couple versions, but personally I believe the Poetic Edda is one of the best. Sure, there’s the Prose Edda, but Snorri Sturrlson adds in some Christianity to the story that wasn’t there originally, and the process of changing the story from a poetic form to a prose form just loses some of the story. As an added bonus, the Poetic Edda provided J.R.R. Tolkien with a good amount of inspiration for The Hobbit, including the dwarves’ names.

2. Hydra

Panel of a Caeretan Black Figure hydria depicting Herakles battling the Hydra, believed to be painted by the Eagle Painter, dating to 525 BCE. This Hydria is part of the Getty Villa collection in Malibu, California.

Panel of a Caeretan Black Figure hydria depicting Herakles battling the Hydra, believed to be painted by the Eagle Painter, dating to 525 BCE. This Hydria is part of the Getty Villa collection in Malibu, California.

The hydra comes from Greek mythology, and is depicted as a many headed immortal water dragon, the number of heads differing based on who told the story, though the number was usually nine. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, the first written appearance of the dragon, the hydra was the child of Echidna and Typhon, two of the more feared monsters of Greek mythology. It lived in Lake Lerna, attacking the villages in the area after the goddess Hera taught it to attack and destroy anything it laid its eyes on. Which made it the perfect monster for Herakles (or Hercules in Latin) to try to kill in his second task of 12 to complete.

As a refresher, if you need it, Herakles was the son of Zeus, the result of one of his many affairs. Hera was understandably upset and told Zeus to banish his son from Mt. Olympus. Herakles still grew into a Greek hero, and one day sought out an oracle, who told Herakles the only way to gain immortality was to complete 12 impossible tasks, which delighted Hera as she saw an opportunity to get rid of Herakles. Slaying the immortal hydra became the second of 12 tasks. It was a nearly impossible one as well, since every time Herakles cut off one of the hydra’s heads, two would grow in its place. Realizing the futility in this way of fighting this way, Herakles calls for his nephew, who starts burning the stumps with fire after Herakles cuts off a head, preventing more from growing. At last he got to the immortal head of the hydra, slicing it off with the golden sword Athena gave him; he then buried the head under a rock to keep it from reattaching. The hydra still lives on, though, in the stars as a constellation. It got its revenge though, as its highly poisonous blood was used to bring about Herakles’s downfall.

3. Apep

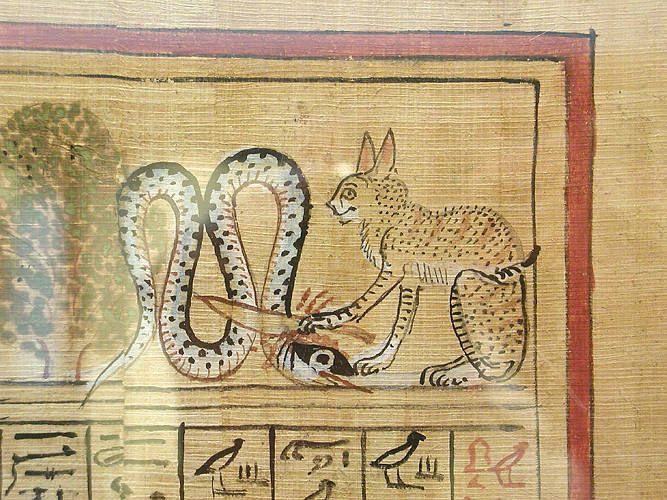

Ra, depicted as The Great Cat Mau, slaying Apep with a knife. Image is from the Papyrus of Hunefer, dating to the 19th dynasty of Egypt.

Ra, depicted as The Great Cat Mau, slaying Apep with a knife. Image is from the Papyrus of Hunefer, dating to the 19th dynasty of Egypt.

Apep, or Apophis as he was known in Ancient Greek, was a serpentine deity from Ancient Egypt. He was the embodiment of true chaos, the Egyptian Big Bad, the other side of the coin to the Ma’at, a representation of popular Egyptian literary motif: order vs. chaos. There isn’t much in the way of an origin story for him, at least not yet, with the most we know of it being that Apep likely came from Ra’s umbilical cord. Ra and Apep were enemies, however, engaged in a battle every night. You see, Ancient Egyptians believed that the sun was Ra’s ship, sailing across the sky every day. As the sun set, Ra’s ship entered the Land of the Dead, and that was when Apep attacked, seeking to destroy Ra and ensure the sun never rises again. They battled all night long, with other deities on the boat to aid Ra, and Egyptian priests would perform rituals and prayers to give aid as well. Ra always won, and the sun always rose, and Apep would retreat back to the Land of the Dead for the next night. The first written appearance of Apep is in the middle kingdom, but most of what we know of him comes from texts from the New Kingdom. The most popular depiction of him, from the Book of the Dead, shows him as a coiled serpent, but a serpent that is almost always under attack or dismembered.

4. Yamata no Orochi

Susanoo slaying the Yamata no Orochi, woodblock print by Toyohara Chikanobu, an artist from the Meiji period

Susanoo slaying the Yamata no Orochi, woodblock print by Toyohara Chikanobu, an artist from the Meiji period

Yamato no Orochi, or just Orochi, is from Japanese mythology, primarily two ancient texts: Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. In both, it is described as an eight-headed dragon with eight tails, as long as eight valleys and eight hills (eight is a significant number in Shintoism, usually affiliated with luck or prosperity). In the main myth, after Susanoo is expelled from the Heavens, he encounters some earthly deities who have lived in fear of the vicious dragon for years, having to give one of their daughters to Orochi for the last seven years, and they were about to have to give up their last daughter. To help, Susanoo turns the daughter into a comb for safe keeping, telling the deities to make eight vats of eight-fold refined liquor and place them on eight platforms. When Orochi arrived to take away the last daughter, it instead dunked its eight heads into the eight vats and drank his fill. Once the dragon was drunk, it immediately fell asleep and Susanoo was able to chop Orochi up, with so much blood flowing from the slain dragon the River Hii changed course. In classic mythology fashion, Susanoo walked away from the battle with a new sword, the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, which came from the tail of Orochi. This sword is later presented to Amaterasu by Susanoo as an apology and the sword becomes one of the Imperial Regalia of Japan.

5. Wyvern

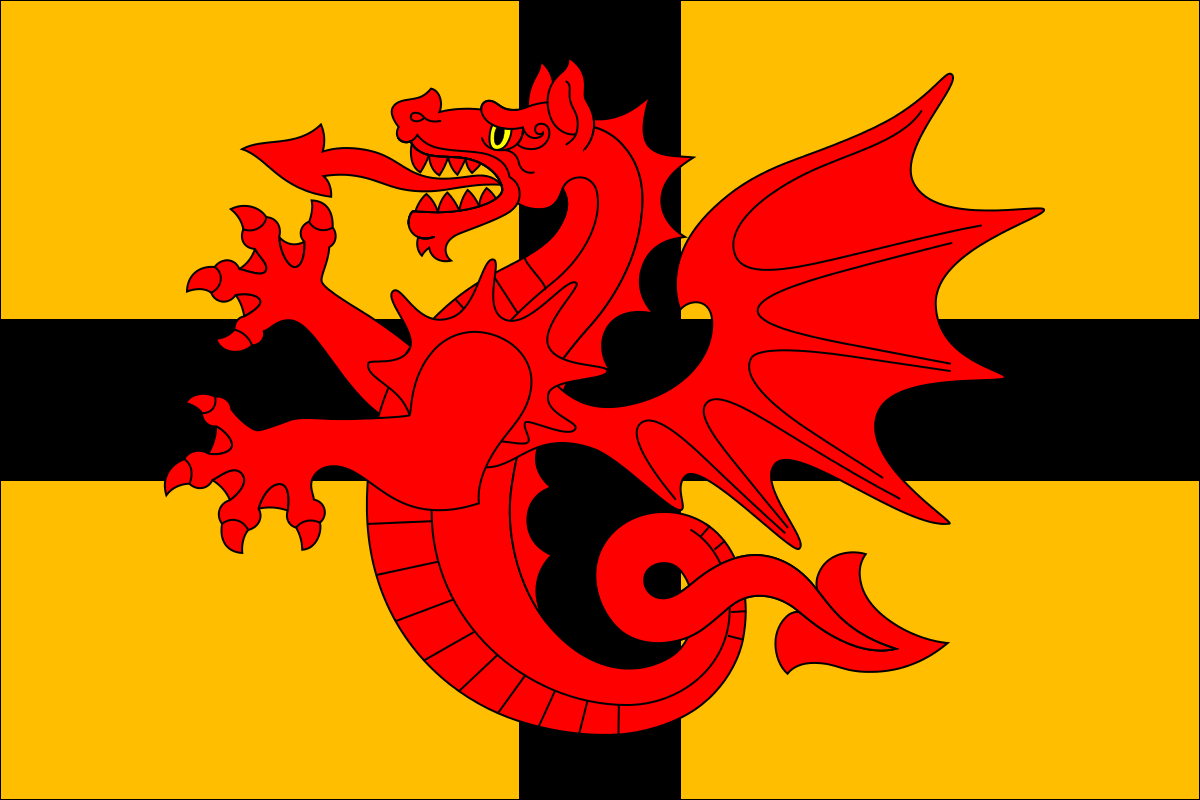

Wyvern depicted on the flag of Trégor, Brittany

Wyvern depicted on the flag of Trégor, Brittany

The wyvern is less one specific dragon and more of a species of dragon. They tend to encompass most European dragons that look like your stereotypical dragon except they only have two legs and a pair of wings. They tend to not breathe fire, either, unlike other folkloric dragons, but they do often have a poisonous tail that’s pronged and barbed. That doesn’t stop them from being all over the place, though, especially in English, Scottish, and Irish heraldry. In heraldry, the wyvern tended to represent strength, protection, and endurance, despite the wyvern itself was said to be very aggressive and spread pestilence. They often have the typical lust for gold that is usually ascribed to European dragons. There are no specific, well-known stories where wyverns take a center point, but they tend to pop up in random regional stories of knights fighting a dragon or are doodled in the margins of manuscripts.

6. Tiamat

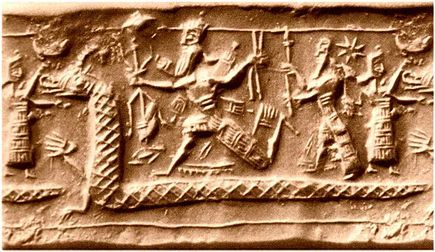

Neo-Assyrian cylinder seal depicting the death of Tiamat, dating back to the 8th century BCE

Neo-Assyrian cylinder seal depicting the death of Tiamat, dating back to the 8th century BCE

No, not that Tiamat. Well, kinda not that Tiamat. She originally comes from Mesopotamian mythology as the primordial sea goddess, the personification of chaos and is often depicted as a sea serpent. She also plays a major role in the Mesopotamian creation myth. From her and Apsu, the primordial god of groundwater, which led to the younger gods Lahmu and Lahamu, which started a domino fall of other deities. I won’t get into the full story here, as Mesopotamian mythology is A Lot and contains several similar sounding names, but through a series of battles and grievances (ancient Mesopotamian deities were not known for being kind or forgiving), Tiamat was killed. Anu, who would become king of the gods, sliced her in half and made her rib cage into the heaven and earth. Her crying eyes became the twin rivers Tigris and Euphrates, her tail the Milky Way. Her story is the root of the rise of Marduk, who is the patron deity of Babylon and eventually the head of the Babylonian pantheon.

If you’re interested in reading entire myths and others including the Epic of Gilgamesh, I highly recommend reading Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others.

7. Y Ddraig Goch

Illustration of Ambrose and Vortigern watching the fight between the red and white dragons, from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 15th century manuscript The History of the Kings of Britain

Illustration of Ambrose and Vortigern watching the fight between the red and white dragons, from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 15th century manuscript The History of the Kings of Britain

Y Ddraig Goch literally translates to “red dragon” in Welsh and is the red dragon represented on their flag. Its story starts in the Mabinogion, where you hear of it trapped, locked in battle with a white dragon. It shows back up in Historia Brittonum, where the Celtic Britons are locked in battle with the invading Saxons. Then-leader of the Britons Vortigern fled and tried to recoup by building a citadel, but it kept collapsing. His wise men tell him that the problem can only be fixed by killing a boy born without a father, but when such a boy is brought in front of Vortigern, the boy tells him the problem is actually two dragons battling under the hill they are trying to build upon. When the dragons are uncovered, the boy tells them that the white dragon represents the Saxons and the red dragon the Britons. The white dragon wins a few battles here and there, but in the end the red dragon will win, and so will the Britons. Later, Geoffery of Monmouth repeats the story in The History of the Kings of Britain, but this time conflating it with the legend of King Arthur, the red dragon representing the coming of King Arthur. Ever since, y Ddraig Gogh has been a symbol of the Welsh and the Celtic Britons, appearing on several standards of multiple Tudor monarchs.

8. Quetzalcóatl

Quetzalcóatl as represented in the Codex Borgia

Quetzalcóatl as represented in the Codex Borgia

Quetzalcóatl is one of the deities of Aztec mythology, the patron deity of a lot, but most importantly, he is considered the creator of humanity. He is one of the more important gods of the pantheon, along with his brothers Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca, and Huitzilopochtli. He’s often depicted as a feathered serpent, when not seen as a man with a feathered snake headdress. In fact, Quetzalcóatl literally translates to “feathered serpent,” and if you’re a fan of hot chocolate you have Quetzalcóatl to thank. He’s the one that brought the cacao tree from their sacred mountain and taught the Toltec women how to make drinking chocolate from it. If you’re interested in reading the stories surrounding Quetzalcóatl, one of my favorites is likely Mesoamerican Mythology: Fascinating Myths and Legends of Gods, Goddesses, Heroes and Monster from the Ancient Maya, Inca and Aztec Mythology by Simon Lopez.

And no, Montezuma II didn’t actually believe that Hernán Cortés was Quetzalcóatl returned. That myth doesn’t really enter the historical record until 50 years after Spain conquered and began colonization of the Aztec empire.

Now that you’ve got a decent background on some of the more famous dragons in mythology and are itching to read some more books about them, or perhaps some other mythological creatures, you may wanna check out our list of mythological creatures in literature or maybe our list of books about dragons aimed towards adults.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/05/100/n/1922564/33582ae7681964cb0d40c8.72464171_.png)

![ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge] ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WHD581-600x330.jpg)