This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Who is Elena Ferrante? It’s an interesting question posed to me often when I’m recommending her work. It’s meant as a straightforward question, and in some ways I could give them a straightforward answer. Elena Ferrante is the author of many internationally acclaimed novels, originally written in Italian and translated by Ann Goldstein. She’s particularly known for her four-volume work, the Neapolitan Novels. But it is actually a little more complicated than that, because Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym used by an unknown author. Is she completely unknown, though? There are glimpses of who she is in her work, particularly her nonfiction, that help readers form a sense of who she is. For many, like myself, that sense feels true and it also feels like enough.

Ferrante’s first novel L’amore Molesto came out in Italy in 1992 (translated by Ann Goldstein into English as Troubling Love in 2006) and her next, The Days of Abandonment, was published ten years later in Italy. These short earlier works shocked and captivated when they were first published in Italy. And it’s no surprise, as they are fiercely intelligent and beautiful novels — utterly enthralling and written with a rare intensity. When her Italian publisher Edizioni E/O couldn’t find a U.S. publisher for her work, they created their own publishing house. Europa Editions was founded in 2005 by Sandro Ferri and Sandra Ozzola Ferri, the owners and publishers of Edizioni E/O, to bring fresh international voices to the American and British markets. Since then, Europa has published books by authors from over 30 different countries and established itself as a leading publisher of international literature.

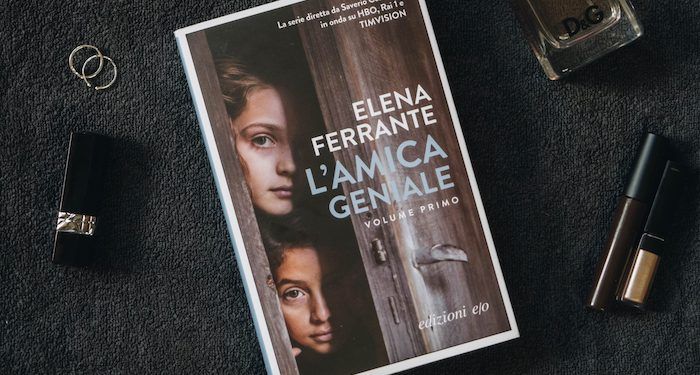

The first of the Neapolitan Novels, L’amica geniale was published in 2011 in Italy and in 2012 as My Brilliant Friend, in Ann Goldstein’s captivating translation. The Story of a New Name and Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay followed, and the final novel The Story of the Lost Child was published in 2015 to a near fever pitch — which is exactly what the excitement around Ferrante’s work has since become known as: “Ferrante Fever.” The quartet have since sold more than 15 million copies worldwide and have been published in 45 languages and counting. The Neapolitan novels follow childhood friends Elena Greco and Lila Cerullo over the course of their lives. Their loves and losses and the constancy of their (sometimes tumultuous) connection are set against the social and political changes in postwar Italy, from the 1950s to present day.

The Lying Life of Adults is Ferrante’s most recent novel, her first in five years since the conclusion of the Neapolitan quartet. Like the Neapolitan novels, The Lying Life is also set in Naples and follows a young girl, Giovanna, from adolescence to adulthood. But The Lying Life is moodier, edgier — an intense and cutting novel of family, class, and womanhood. Giovanna’s story begins when she overhears her beloved father saying that she has the face of her estranged and hated Aunt Vittoria, which she takes to mean that she is ugly. This remark opens up a crack in Giovanna’s life and she begins a desperate search for her aunt, throwing her headlong into the lives (and lies) of the adults she had loved and trusted mere moments before.

In Reading Color Newsletter

A weekly newsletter focusing on literature by and about people of color!

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Why Does She Use the Name Elena Ferrante?

Ferrante has said in numerous interviews, done by email and through her publisher, that she protects her identity to remove the pressures and obligations, to avoid being “tied down to what could become one’s public image. To concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies.” This, she has always said, allows her novels to speak for themselves. In an interview with Vanity Fair, Ferrante describes the decision and its impact on her life:

I simply decided once and for all, over 20 years ago, to liberate myself from the anxiety of notoriety and the urge to be a part of that circle of successful people, those who believe they have won who-knows-what. This was an important step for me. Today I feel, thanks to this decision, that I have gained a space of my own, a space that is free, where I feel active and present. To relinquish it would be very painful.

I was particularly struck by her musings in an article for the Guardian about a painting in the Pio Monte della Misericordia, in Naples. The 17th century painting that has captured Ferrante’s attention is of a nun, “with hands joined, eyes closed and an ecstatic expression.” The painting is by an unknown artist, and Ferrante writes that ever since she was a young person, she liked the term unknown. Not knowing the artist liberates her from thinking about the artist and gives her space to concentrate only on the art. She goes on to add that the artist while unknown to her in name, is in reality a figure she knows intimately through their art, their “only true name.” It’s a stunning statement, that seems to capture so much of what Ferrante is doing with her own work.

It would not be a pseudonym, that is, a false name; it would be the only true name used to identify her imaginative power, her ability. Every other label would be problematic, would bring into the work precisely that which has been kept out of it, so that it would stay afloat in the great river of forms.

What Can We Learn From Her Nonfiction?

In addition to her fiction, Ferrante has also released Frantumaglia, translated by Ann Goldstein, a collection of letters, essays, reflections, and interviews that together offer readers a glimpse into her writing desk and thoughts. And in 2018, Ferrante began a series of articles for the Guardian (including the one I referenced above) with the agreed upon conditions that her column would last one year and that the editors would pose a question to her for each column. These articles have since been collected and published in the book Incidental Inventions, also translated by Ann Goldstein. In the column, Ferrante reveals pieces of herself, and while they might feel like they skim only the surface of who she is, they are immensely captivating.

She is Italian

Ferrante’s books feel to me deeply connected to Italy and many readers now travel to Italy, and Naples specifically, because of Ferrante. And yet she writes that while she loves her country, she has no patriotic spirit and no national pride. Her focus is on the Italian language. She even jokingly writes that she doesn’t eat much pizza or spaghetti, or gesticulate or talk loudly. National characteristics, she argues, are “simplifications that should be contested.” Instead her focus is on the language.

Being Italian, for me, begins and ends with the fact that I speak and write in the Italian language. Put that way it doesn’t seem like much, but really it’s a lot. A language is a compendium of the history, geography, material and spiritual life, the vices and virtues, not only of those who speak it, but also of those who have spoken it through the centuries. The words, the grammar, the syntax are a chisel that shapes our thought. Not to mention our literary tradition, an extraordinary refinery of raw experience that has been active for centuries and centuries, a reservoir of intelligence and expressive techniques; it’s the tradition that has formed me, and on which I’m proud to have drawn.

She is a Mother

Ferrante discusses motherhood often in her nonfiction pieces and has mentioned her daughters and at least one grandchild. She details the experience of bringing her children into the world and the ways that pregnancy was both a joy and immense difficult. Her first pregnancy she characterizes as an “anxious mental struggle” careening between joy and terror. She also writes that she took care of her newborn by herself, without help and very little money. She wanted desperately to write but was exhausted. Slowly motherhood and pregnancy become a key source of joy in her life but she writes often that she understands the decision to not have children too.

Today I think that nothing is comparable to the joy, the pleasure, of bringing another living creature into the world.

She Loves Translators

This last point may seem like a small point in comparison to the first two, nationhood and motherhood. But just as constant in her pieces are Ferrante’s deep devotion to language, writing, and reading but also to translation. As someone who reads Ferrante in translation, specifically through the masterful work and care of the great Ann Goldstein, it seems a fitting and necessary conclusion. She says that her only heroes are translators and she “especially love[s] those who are experts in the art of simultaneous translation.” She admires in particular when they are also passionate readers and propose translations, continuing to spread the joy of language and literature all around the world.

Translators transport nations into other nations; they are the first to reckon with distant modes of feeling. Even their mistakes are evidence of a positive force. Translation is our salvation: it draws us out of the well in which, entirely by chance, we are born.

Has Anyone Tried To Discover Who She is?

The items listed here are a few of the pieces of information Ferrante has shared over the years with readers — glimpses of her own life experiences and creative interests that have shaped her work. But a few have tried to discover her identity over the years. Scholars and journalists have proposed numerous authors that they believe could be Elena Ferrante, but the most explosive news related to the search for Ferrante came in 2016. In October 2016, Italian investigative journalist Claudio Gatti’s piece “Elena Ferrante: An Answer?” was published by Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore, the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and on the French website Mediapart. An English version of the investigation was simultaneously published by The New York Review of Books. In his article, Gatti points to translator Anita Raja as the writer behind Ferrante’s legacy.

Raja is a Rome-based translator who has worked over the years for Edizione E/O. Gatti examined both Raja’s financial and real estate records and argues that the extensive increase in payments made to her by the publishing company over time and her large real estate purchases make a powerful case that Raja is behind Ferrante. Interestingly enough, Raja is married to writer Domenico Starnone who has often been speculated as the writer behind Ferrante. Starnone’s work is also published by Edizione E/O and Europa Editions, in Jhumpa Lahiri’s English translation.

In the article Gatti writes, “In an age in which fame and celebrity are desperately sought after, the person behind Ferrante apparently didn’t want to be known. But her books’ sensational success made the search for her identity virtually inevitable. It also left financial clues that speak by themselves.” While it may have been inevitable, Gatti’s article was met by a lot of criticism by readers and authors alike who decried the invasion of privacy and lack of respect for Ferrante’s wishes. In the years since, it seems as if this protective instinct has kept the speculation at bay. Ferrante’s fans seem interested to know her by her art, her “only true name.”

Interested in reading more about Elena Ferrante? You can browse our Elena Ferrante archives.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/06/835/n/1922564/8e601b95681a5cf04194c6.14070357_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/05/100/n/1922564/33582ae7681964cb0d40c8.72464171_.png)

![ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge] ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WHD581-600x330.jpg)