This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

A few weeks ago, I read Annika Barranti Klein’s article, Did Maurice Sendak Hate Children? It was funny timing, because I had just picked up my phone to scroll after reading all about Maurice Sendak in children’s book historian Leonard Marcus’s book Minders of Make-Believe. While I don’t necessarily disagree with the points Annika makes, I do wonder if there are other reasons that people might think he doesn’t like children. His crotchety personality and the fact of his being gay could very certainly play into it, but I’m inclined to think that it’s thanks to some of the Sendak quotes that tend to circulate.

Sendak might say things like “I don’t write books for children. I write them for myself. Children happen to like them,” and then that will get picked up, circulated, and somehow becomes proof that Sendak didn’t want to write for children. In that same interview, of course, Sendak disagrees with the idea. He says, “People tend to take children’s books less seriously as a literary form. Those of us who work on children’s books inhabit a kind of literary shtetl. You always have the sense that whatever you’re saying is considered less because of its form. It’s funny: you never hear William Faulkner described as a writer of adult books. But people like me are described as writers of children’s books.”

Maybe some readers are surprised that people tend to talk down to children’s book writers, but as a writer and editor of children’s books, I can tell you that they’re often considered to be lesser than adult works. While seven- (and eight-!) figure advances for bestselling YA novels sometimes make headlines, they make headlines because they’re rare, and picture book advances are some of the lowest in the industry. Sendak himself doubted that the library to which he had loaned his papers took him seriously as an artist, which is one of the reasons his estate executor chose to take the papers back after his death.

Some authors come to regret writing children’s books at all. It’s common knowledge that A.A. Milne’s son, the real Christopher Robin, wasn’t a fan of Winnie the Pooh, but Milne himself endured quite a bit of mockery. Dorothy Parker, whose review of the book would become one of her most famous pans, cited the line at which she, affecting a baby voice, “frowed up.” Milne, an accomplished playwright and poet before Winnie the Pooh, would write in the forward for one of his later plays that everything he wrote was always judged as being written by the author of Winnie the Pooh, saying that he couldn’t even mention a cat sitting on a mat, because “[i]ndeed if I did say that the cat sat on the mat (as well it might), I should be accused of being whimsical about cats; not a real cat, but just a little make-believe pussy, such as the author of Winnie-the-Pooh invents so charmingly for our delectation.”

The Kids Are All Right Newsletter

Sign up to The Kids Are All Right to receive news and recommendations from the world of kid lit and middle grade books.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use

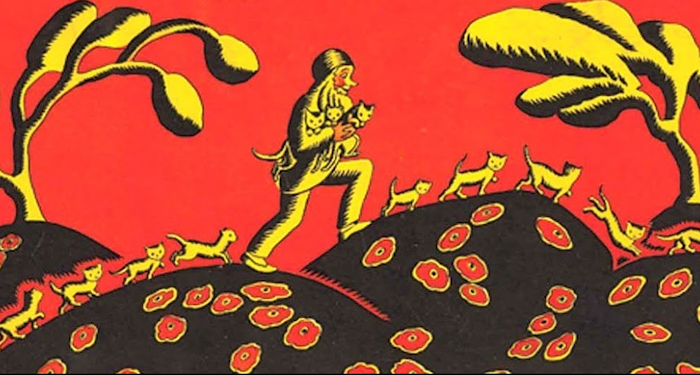

It could be because children’s books are a relatively new product category. While people have been publishing books for children since at least the 1600s, most of these books were highly moralistic, hardly stories at all, or simple concept books, like alphabet books. Little Women (1868), by Louisa May Alcott, is often considered the first American novel written for children, and there wasn’t a true American picture book until Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág, published in 1938.

Both Alcott and Gág had career goals outside of children’s books. Alcott wanted to write serious novels for adults and never quite got over the fact that she was, as she felt, stuck writing for children in order to make money for her family.

In Minders of Make-Believe, Marcus tells a story about Alcott’s publisher taking advantage of her low opinion of her own work. When Alcott, on the success of Little Women, asked for a higher royalty rate on her next book, her publisher, as Leonard says played “mercilessly on Alcott’s self-doubt and grimly [forecast] the worst for An Old-Fashioned Girl, he reminded her that as a ‘second class storyteller’ she ‘ought not to expect more….Surely you don’t want an additional percentage on a failure.’” Alcott’s opinion of her own genre (and her own writing!) was so low that she was talked out of the higher paycheck that she dearly needed. She did, eventually, get that higher royalty rate, but I don’t think she ever reconciled herself to writing for children. She published a rather serious adult novel immediately following An Old Fashioned Girl, but it wasn’t nearly as successful as her books for children, and she wouldn’t try to write another adult book under her own name again, instead trying out different pen names and publishing anonymously.

Wanda Gág took a slightly different path. She was an artist and printmaker who moved to New York to in the hopes that it would improve her career. She had a few well-attended shows, and at one of them, was “discovered” by a young editor at a publishing house that had just formed its children’s publishing team. According to Leonard Marcus, the editor saw Gág’s drawings and approached her to ask her to write a children’s book. In Gág’s diary that day, she scoffed at the idea, but after a while, decided that it might be a way to make some extra money.

Ernestine Evans, the editor, said that she saw in Gág’s work “the wonder of ordinary things,” and I like to think that it didn’t take Gág very long to realize the same things. She could make washtubs or kitchen chairs seem magical, and soon she’d bring that same sensibility to her rather fantastical picture books.

Millions of Cats, her first book, is the longest running American picture book in print. Gág, for her part, would continue creating fine art, but also threw herself into children’s books. She wrote both her own books and also translated European fairy tales. Gág went from thinking that children’s books were easy money to caring so much that children might think that Disney’s Snow White was the definitive version of the story that she translated and illustrated her own and went on to publish several volumes of fairy tale translations.

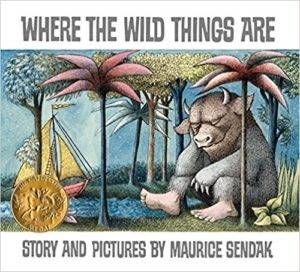

We’ve just passed the 150th anniversary of Little Women, and we’ll soon be upon the 100th anniversary of Millions of Cats. Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are is an undisputed (though sometimes challenged) classic. While there will likely never be quite the same prestige to writing children’s books as there is to writing other genres, I think we’re lucky to live in a time when most children’s book authors are proud of their work, which is, whether they like it or not, thanks to the likes of Alcott, Gág, and, of course, Sendak.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/03/28/775/n/1922564/22119f9d67e6de01304208.95605728_.png)