Monster House is the only movie I’ve ever thrown in the garbage. I found a copy at the grocery store years ago and excitedly assumed that it would be a fun watch for the evening, since I had heard such good things about it. Then I saw it. I saw its fatphobia and its misogyny and its insulting, mean-spirited messages packaged for children. I was shocked and disgusted when the credits rolled, so I popped out the DVD, put it back in its case, and marched outside to throw it in the garbage can.

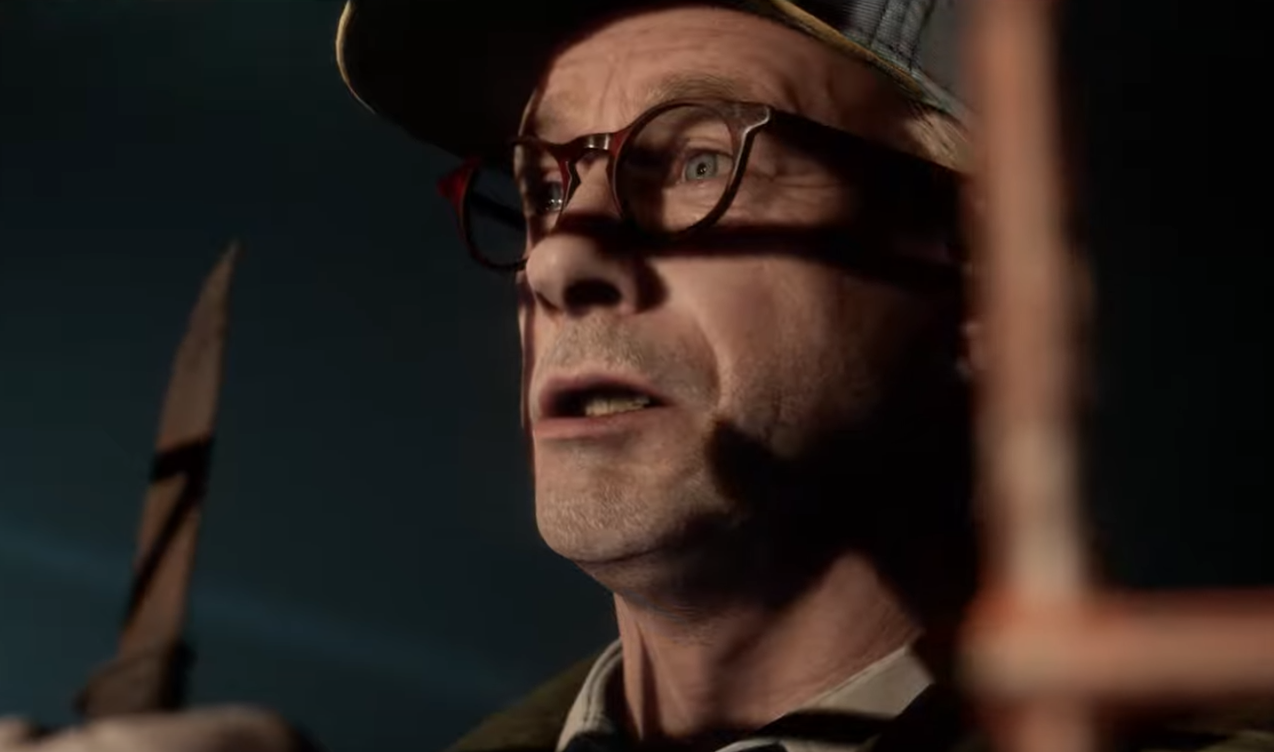

Every time Halloween rolls around, 2006’s Monster House pops up on people’s lists of recommended gateway horror. In classic kids’ horror fashion, a ragtag group of friends—DJ (Mitchel Musso), Chowder (Sam Lerner), and Jenny (Spencer Locke)—must defeat the evil supernatural forces that live across the street from DJ’s house. The “monster house” in question is where the neighborhood crank Horace Nebbercracker (Steve Buscemi) lives. It turns out that the house is possessed by the spirit of his late wife, Constance (Kathleen Turner), who died on the site when the house’s foundation was being laid.

It is a deeply fatphobic and misogynistic movie, with every character contributing to its spiteful rhetoric. Whenever anyone asks for gateway horror—movies meant to introduce young viewers to the genre without scarring them for life—Monster House inevitably finds its way into the conversation. I’m here to tell you why it shouldn’t.

Thanks to c-PTSD, my memory has more holes in it than a Junji Ito manga. It’s usually only the painful moments that I retain. Gone are the happy times; the fun, the laughter, the pleasure. I don’t remember any of those. But the memories that hurt…those are always at the ready, waiting to slash the soles of my feet like shards of broken glass stuck in the mud. As a result, I remember every single time I’ve been mocked for my size. I’ve been fat for pretty much my whole life, which means I’ve been made fun of for being fat for pretty much my whole life. The first time I remember dissociating from the bullying was when I got my third-grade class picture taken. The photographer told me to smile and called me “pretty lady,” at which point the meanest kid in class (hi, Trevor) started laughing and derisively repeating the photographer’s words. I floated away from his laughter as a form of psychological escape, because I knew what he meant: I was fat, so I couldn’t possibly be pretty.

Despite my size—I say “despite” to combat the inevitable fatphobic skepticism—I’m very athletic. I played softball for 13 years. When an opposing team loudly mocked my “jelly rolls” during a high school game (which my team won, thank you very much), I dissociated once again. I floated outside myself, observing but not feeling the stings of their insults until they stopped and it was safe to reintegrate with my body. That’s the thing about being fat. You never feel safe or at home in your body, because the world tells you that it’s something to be ashamed of; something to be repulsed by; something to fear and avoid at all costs. You’re never supposed to feel proud or strong or—God forbid, sexy—in a fat body. You’re supposed to worship at the altar of thinness and flagellate yourself every day for being too big for the box they want you to fit into.

So when I saw that venomous bullying in a movie meant to introduce kids to the horror genre—a genre for the outcasts, for those who don’t fit in, for those who are desperately seeking a welcoming home—I felt like I’d been slapped in the face. I was right back in front of that photographer, being laughed at for daring to believe that I could be pretty. I was right back on that softball field, being laughed at for existing as a fat person in a place where only thin people are allowed. Now, in the comfort of my own home and my own beloved film genre, I was being laughed at yet again. Existing as a fat woman made me the villain. Being fat made me the punchline.

Fans often praise Monster House for its ‘80s throwback style. While that’s certainly true of the ‘kids vs. monsters’ premise, it’s also true of the film’s abhorrently casual fatphobia. Every single fat character is a walking punchline centered around food, clumsiness, stupidity, or some combination of the three. Worse still is the fact that fatphobia isn’t just used as comic relief: it’s baked into the very fabric of the narrative. The villain—the titular monster—is a ravenous, ill-tempered fat woman. She may exist as a house for most of the film, but you can’t ignore the fact that this giant, hulking, “ugly” house—as it’s described by the film’s skinny characters—contains the soul and personality of a deceased fat woman. This fat woman is the monster who must be defeated.

Rewatching Monster House for this piece was difficult. I noticed mean-spirited fatphobia before the very first scene. The title card becomes so big that it can’t even fit on the screen, implying that Constance is too large to be contained within the borders of the animation cels. First-time viewers will miss the incessant jabs at Constance’s weight and supposed ugliness, but they’re there: our first view of the titular house emphasizes the fact that it is old, discolored, and crooked; its windows are asymmetrical, with different shapes and uneven placements on the house. Even as a sentient building, Constance is misshapen. A fat woman begets an ugly house, according to the film’s creators, and the viewer is primed before we even see Constance to think of her as being unnatural—monstrous, even—in her own body.

The film’s fatphobia isn’t confined to Constance’s character. DJ is the hero of the piece, and as in most beloved ‘80s-style kids’ movies, he has a fat best friend who serves as the comic relief. Everything with Chowder (yes, he’s even named after food) comes down to his appetite, his clumsiness, his stupidity, or an egregious combination of the three. Chowder gets winded doing some fancy dribbling with his newly purchased basketball, and the same thing happens later when he and DJ are running through their neighborhood. Chowder has to take a break, bending over and wheezing to emphasize just how physically unfit he is as a fat person.

In another scene, DJ yells at him to run, to which Chowder replies that he is running. Again, the fat character is so out of shape that his running doesn’t even qualify as such. He is too slowed down by his weight to keep up with the thin characters. (Fun fact: we did speed trials on my junior high softball team, and I was both the largest and the fastest girl on the team. There is no direct correlation between weight and athletic ability.)

Chowder is constantly talking about food—he looks forward to getting candy when they go trick-or-treating, and he mentions his favorite taco stand when he tries to hit on Jenny, the skinny girl who of course becomes DJ’s love interest rather than Chowder’s. Skinny characters call Chowder things like “Porky” or “pork chop.” When he’s not talking about food or being insulted for his weight, he’s making mistakes that show how stupid and clumsy this movie thinks fat people are. When the kids attempt to fool the house using a decoy trick-or-treater (a vacuum cleaner disguised as a child), Chowder has to be reminded to plug the vacuum in to make it move forward.

In one of their showdowns with the house, Chowder keeps shooting the cold medicine designed to put Constance to sleep at the wrong spots because he’s so scared. (This moment is doubly problematic; not only is Chowder depicted as a clumsy coward due to his size, but also one of the most suspenseful moments in the film hinges on whether they can successfully drug a fat woman into compliance.) Chowder accidentally turns on a backhoe when he and DJ are hanging out in a construction zone, and DJ has to turn it off for him.

Because fat people’s bodies are bigger than what society deems acceptable, Monster House argues that we must not be able to use them properly. That assumption, and the film’s constant emphasis on Chowder being a “moron” (again, using the film’s own words), betray an insidious ableism at the core of the film. Not only are fat people assumed to be disabled because of their size, but that disability must also mean that they have to be rescued by the thin characters who know how to navigate the world better than the fat characters do.

That presumed clumsiness is never more obvious in the film than in Constance’s death scene. Horace found Constance while she was performing in a “freak show.” The movie wants you to think he saw her as more than just a sideshow attraction, but he never humanizes her; he only fetishizes or infantilizes her. At the end of the film, when our ‘heroes’ confront the “monster house,” Horace says to her: “You’ve been a bad girl, haven’t you? You’ve hurt people!” He doesn’t talk to her like his wife; he talks to her like a disobedient child.

When Horace rescues Constance from the sideshow (again, Monster House wants you to believe that fat people need thin people to swoop in and save the day), he hitches the cage she’s trapped in to his truck and tows her away. Rather than freeing her and letting her ride in the truck with him like a human being, he treats her like so much cargo or like a wild animal that has to be caged up to protect the rest of the world from it.

Even in death, the film won’t let Constance escape that damn cage. As she and Horace build their dream house, trick-or-treaters come by the construction site. Constance—“irrational” and defensive after being pelted by produce at the sideshow—yells at them in an animalistic, unintelligible wail. She gets winded just from yelling, and when she tries to attack the trick-or-treaters, she falls backward into a pit, turning on a cement mixer in the process. She falls to her death and is encased in cement; she is buried, along with her hopes and dreams, in the foundation of her own home.

This scene lays bare Monster House’s entire disgusting thesis: fat people, especially fat women, are mean, stupid, and clumsy. Constance screams like an animal at children for no reason (at least, that’s what the movie wants you to think). Then, because she’s so fat and therefore must not be in control of her own body, she causes her own death due to her ungainly movements. To add insult to injury, the shrine that Horace builds to Constance is protected by her sideshow cage. She is a monster, even in death. Her large cement tomb is just another oddity to gawk at; it’s not a place of remembrance for a loved one or a memorial for a human being who died due to construction site safety issues. It’s a cheap jolt, a shock to the system; Constance’s burial ground is a punchline to the 91-minute joke that isMonster House.

Whether Constance is in human or house form, you can feel this film’s hatred for fat women in every single frame. The house cruelly eats anything and everything: beloved toys, police cars, dogs, even children themselves. Constance is fat, which must mean she will eat everything in sight. Her fatness makes her ravenous, vicious, and selfish. She takes pleasure in taking things away from others to satisfy her own appetite. Once DJ, Chowder, and Jenny figure out what’s really going on inside the “monster house,” they suss out Constance’s new biology.

The entire house is one big mouth. The jagged wooden slats that appear when the doors open are her teeth; the chandelier is her uvula; the rug that extends from the open door to catch unsuspecting victims is her tongue. Every open space in the house is part of one giant mouth, because that’s all fat people are to the creators of this film: giant mouths that do nothing but eat. When we’re not eating, we’re sleeping, as the kids discover as they walk through the house and hear snoring—violating Constance’s body once more, continually desecrating her grave by trespassing where they’re not welcome.

Though the film mocks all its fat characters, Monster House reserves its most virulent fatphobia for Constance, and the way the characters discuss Constance’s body is just as fatphobic as the way the film depicts the house. When the kids find pictures of Constance, they talk about the rumor that her husband “fattened her up and ate her.” The idea of “fattening” someone up implies that being fat is an unnatural state; that you have to make deliberate choices in order to make someone fat, which leads to the fatphobic (and erroneous) argument that if fat people would simply eat right and exercise, they wouldn’t be fat anymore.

Thin women aren’t spared from the film’s misogyny any more than Constance is. With the possible exception of DJ’s mom (Catherine O’Hara), every thin woman in the film is duplicitous and conniving. When Jenny meets DJ and Chowder, she asks them, “Are you guys mentally challenged? If you are, I’m certified to teach you baseball.” Not only is this another ableist insult that’s meant to elicit laughter, but it also implies that Jenny is a self-centered climber who collects “altruistic” activities as a means to an end—getting into a prestigious school—rather than as an act of kindness meant to help other people.

When we first meet Jenny, she’s selling candy door to door with a lilt in her voice and a huge smile on her face. Her faux sweetness and innocence drop quickly when she realizes that DJ’s babysitter Zee (Maggie Gyllenhaal) isn’t buying her act. For her part, Zee is a terrible babysitter who blackmails DJ into compliance and lets her boyfriend Bones (Jason Lee) bully him. Later on, Zee uses a dorky teen boy—Skull (Jon Heder), a fat gamer who steals food from Chowder in yet another instance of fat people being obsessed with food in this movie—to try to make Bones jealous.

Chowder’s mom, who is mentioned only in passing, is strongly implied to be having an affair with her personal trainer (this detail about his occupation adds another concerning layer to Monster House’s issues with fatness and perceived attractiveness). All three female characters are depicted as liars who present false faces to the world—at least, the people in the world who matter, i.e., men—in order to accomplish their selfish goals.

DJ, the thin white hero, is pretty much the only character who escapes the film’s criticism. The kids call the police for help in defeating the “monster house,” and once again, a fat character whose sole defining trait is his fatness—along with all the negatives that supposedly go hand-in-hand with his size—shows up to make sure viewers know exactly how laughable fat people are. Officer Landers (Kevin James) immediately makes a joke about eating doughnuts instead of working.

Later on, when his partner Officer Lister (Nick Cannon)—a thin man and the only Black character in the film, whose major personality trait is his incompetent buffoonery as he literally waves his service pistol around and misunderstands everything he is told—hears the house growling, Landers insists that it’s his stomach rumbling instead because he’s so starving. At the end of the film, after both policemen have “escaped” the ruins of Constance’s destroyed body, Landers immediately suggests they steal candy from children so they can have something to eat. With these two cop characters, Monster House hits the lazy and offensive comedy writing trifecta: a Black man who is less intelligent than the white people around him, and the fatphobic one-two punch of a cop who likes doughnuts and a fat man who can’t stop talking about food.

All these jokes at fat people’s expense add up, and they make for a painful watch. Most hurtfully, Monster House argues that loving a fat person is a form of prison. When Horace flees the house with the kids, Constance detaches from her foundation and turns into a bipedal mouth, roaring and snarling and chasing them with what we’re supposed to see as inhuman fury. With triumphant music playing (and DJ saving Chowder just in the nick of time, because the film couldn’t resist having the thin hero save his fat friend one more time), the kids demolish the house. They destroy Constance’s body. Her spirit departs (silently, of course; Constance has no agency in this film beyond the unthinking hunger and rage that the writers give her). And what is Horace’s response to seeing his beloved wife killed by virtual strangers?

“Forty-five years. We have been trapped for 45 years. And now we’re free. We’re free! Oh, thank you, friend! Thank you all! We’re free!”

With this supposedly heartwarming speech, Monster House turns subtext into text: loving a fat woman is a curse. It is a trap. It leads to a life of misery; if you love a fat woman, you are bound to a ravenous, bitter, hideous monster when you could be out-living your real life instead. Simply typing those words makes me tear up…how many times have I feared this exact thing? How many times have I avoided romance or friendship because I thought people wouldn’t want the burden of dealing with a fat person or the embarrassment of being seen with a fat woman? Chowder even suggests that Horace find someone better now—someone thinner—like “a nice beach house.” How many times have I feared a partner would replace me with someone thinner, therefore prettier and worthier of love? All because society tells me that I do not deserve the same things that a thin woman does. I don’t deserve respect, compassion, love, or desire. As Monster House makes abundantly clear, fat women don’t count as human.

I shouldn’t have to explain to you why fatphobia matters. I shouldn’t have to tell you that it’s harmful to center a kids’ film around the idea that fat women are hideous, clumsy, ill-tempered monsters. Teaching people to hate women and fat people isn’t a harmless bit of Halloween fun; it’s a harmful and dangerous ideology that needs to be called out wherever you find it, even if you find it in a movie you grew up loving. I’m sorry I have to be the one to tell you this, but there is no world in which this film is anything other than a hatefully fatphobic and misogynist movie trying to disguise itself as a charming bit of gateway horror.

Just as I shouldn’t have to explain to you why fatphobia is wrong, I shouldn’t have to steel myself against the inevitable flood of fatphobic, misogynistic hate I will get for writing this piece. But I am. I’m doing my best to prepare for the jokes and insults about my size and my looks; I’m getting ready to hear a frenzied version of the constant refrain I live with, telling me that I’m ugly and asking how I dare think otherwise. I shouldn’t have to hope that my dissociative state will kick in and protect me from the abuse, but I do. And I’m sure it will, because that’s what I’ve been trained to do my whole life: disconnect from a body that society deems hideous and wait until it’s safe to come back to it, knowing full well that it’s never really safe…not in a world that holds up fatphobic films like Monster House as the gold standard for children’s entertainment.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/06/835/n/1922564/8e601b95681a5cf04194c6.14070357_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/05/100/n/1922564/33582ae7681964cb0d40c8.72464171_.png)

![ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge] ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WHD581-600x330.jpg)