Cinephile loner Eric Binford is not Cody Jarrett, the iconic cinematic gangster James Cagney portrayed in White Heat (1949), but Binford thinks he’s Jarrett. Binford’s love interest Marilyn O’Connor is not Marilyn Monroe, although she becomes the late star in Binford’s mind. Real-life is not a movie, yet Binford can’t tell the difference. Tragedies result when Binford’s warped fantasies disrupt his and others’ realities in Fade to Black (1980), a feature considered a slasher film, even though it isn’t.

The Slasher Film that Wasn’t

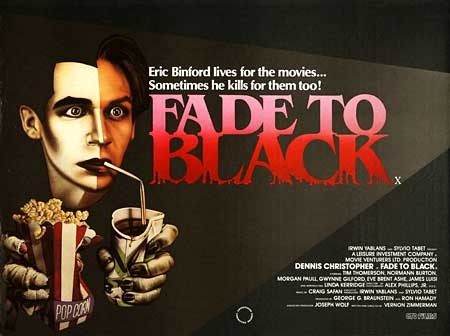

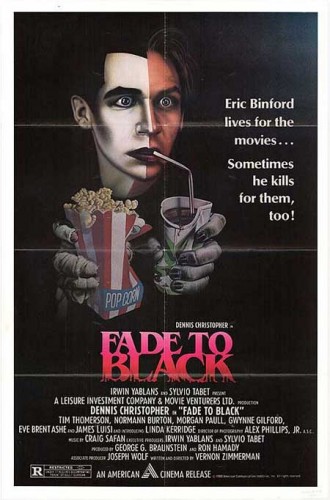

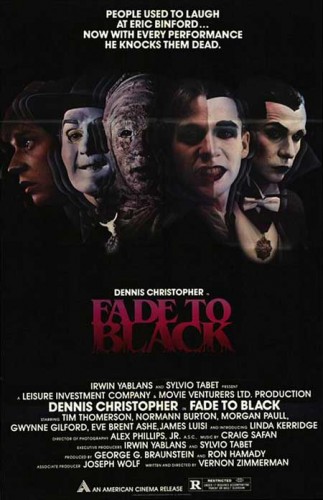

Marketed as a slasher film when first released, Fade to Black could fit into multiple horror subgenres. Eric Binford’s descent into madness leads him to disguise himself as various classic movie villains. Donning these personas allows Binford to recreate classic movie scenes to inflict fatal revenge on tormentors. Such a wild horror tale hardly mimics the killer-with-a-knife-ax-pitchfork-chainsaw mayhem associated with the 80’s slasher cycle. Vincent Price’s Edward Lionheart and Anton Phibes performed their Me-Decade versions of Binford’s vengeance in Theatre of Blood (1973) and The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971).

Eric Binford does no slashing in the film, as the path of vengeance involves using a Colt .45, a Tommy gun, and even causing cardiac arrest. One victim dies by accident. Binford chooses not to wear a hockey or Halloween mask, but he dresses up as The Mummy and Count Dracula, two classic monsters considered outdated during the slasher cycle. At least the Golden Age creatures maintain the film’s partial link to the horror genre.

And the link is partial. Binford’s mayhem doesn’t always involve him donning horror-inspired outfits. Besides dressing up as western hero Hopalong Cassidy, his first fatal assault mimics Richard Widmark’s demented Tommy Udo character from the film noir classic Kiss of Death (1947).

Further pushing aside Binford’s horror bonafides is the character he becomes: Cody Jarret, a gangster. The central fantasy figure Binford idolizes doesn’t come from a horror film.

Is Fade to Black even a horror film, much less a slasher picture? Perhaps it hovers on a psychological crime thriller’s rim while coming close to horror. The film’s seemingly disparate elements subtly highlight the main character’s dissociative identity disorder that veers into psychopathic behavior.

Ultimately, the “slasher” is a deeply troubled human being, and Fade to Black’s narrative reflects a tragic character study airdropped into the horror genre.

The Killer Who Wasn’t There

Eric Binford represents the proverbial person alone in a crowd. His inability to connect with the people around him – friends, family, co-workers – prompts him to live a reclusive existence, one where celluloid heroes surround him. Binford loses himself in movies, watching old Hollywood classics on a black-and-white television and through the old collector’s lament, the 16mm film projector. His abusive (and the dialogue hints sexually abusive) aunt berates him for throwing away what little money he earns working for a distribution company on rare film prints.

He can’t stay in his room 24/7, but besides work, Binford continues his escapism by visiting retro theaters and self-medicating on triple bills. The sad existence gives him some solace from a harsh world outside, but Binford denies himself the chance to deal with his social troubles. Losing oneself in a fantasy world of celluloid villains and heroes makes taking steps to adjust to the real world more challenging. The further he pulls away, the harder the steps to come closer become.

Adding to the dilemma, Binford identifies with villains instead of heroes, turning problems into nightmares.

Celluloid Villains and Heroines

Most disturbing, Binford identifies with cinematic killers. While he doesn’t spend much time enjoying horror films as much as crime melodramas, his hat-tip Dracula and Mummy disguises show an appreciation for dark cinema. Hopalong Cassidy serves as the one outright hero Bindford appreciates, but he turns the B-western hero into a villain. The affinity for Cody Jarrett might be the most unnerving of all, as Jarrett’s homicidal gangster becomes a dual personality for Bindford when the young man loses his grip on reality.

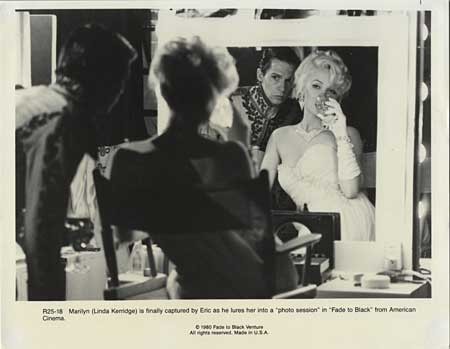

A disastrous planned date with love interest Marylin O’Connor ends with Binford being stood up. Afterward, he slips into a depression that sends him over the edge. Binford’s held a tenuous hold on reality before the disappointing night as Binford did not set up a date with Marylin O’Connor. He set one up with “the real” Marylin Monroe.

Binford’s doesn’t merely feel attraction to O’Connor because she bears a resemblance to Monroe. Subconsciously, he believes she is Marylin Monroe. Any connection with O’Connor comes from the belief he’s bringing his celluloid Marylin Monroe fantasy to life. That delusional attraction coincides with Binford’s transformation into gangster Cody Jarrett. When the Monroe fantasy does not and cannot turn into a reality, Binford doubles his focus on becoming Cody Jarrett and, sometimes, other villains to numb the pain and escape reality. He’s also embodying all the “bad habits” villains display.

Villains display a twisted form of empowerment, although empowerment might be the wrong word. Subjugation and victimization fit better. Villains attempt to get what they want through manipulation, duplicity, threats, or outright violence. The behavior’s severity depends on the character. Wall Street’s (1987) Gordon Gekko’s harm is mostly financial. White Heat’s Cody Jarrett presents a far more dangerous influence since Jarrett is outright homicidal.

Fade to Black’s relatively short running time makes character development challenging. The horror/quasi-slasher film has to fit in a body count that gnaws away at other narrative elements. Audiences might not fully understand why Bindford relates so much to Jarrett, and an overwhelming number of teenaged ticket buyers likely never saw White Heat. Likely, the Binford character connected to Jarrett’s Oedipal fixations, which made him sympathetic and emphatic to the gangster.

A murderer who kills without remorse to furthering a life of thievery and debauchery doesn’t represent the best role model for someone slowly losing grip on reality. Lose reality and lose the message.

Warner Bros.’ classic gangster films portrayed their title characters as amoral blue-collar figures becoming corrupt to take a piece out of a corrupt system. The movies generally ended with the gangster facing the final justice that a life of crime delivers. Not every crime film fan gets the morality message or warnings, and they could put too much faith into the gangster’s stick-it-to-the-machine mentality. Eric Binford represents a melodramatic escalation of villain worship.

Final Failure on Hollywood Blvd.

Fade to Black and Eric Binford meet an end that replays Cody Jarrett’s demise, with the original Mann’s Chinese Theater on Hollywood Blvd. replacing the no-name gas storage tank at White Heat’s finale. Victimization and isolation factored into Binford’s mental decline, but he made several bad choices, starting with a retreat from reality into to a blurred fantasy existence. Choosing to imitate murderers and carry out homicidal fantasies makes Binford an unsympathetic and disturbed villain. If he receives any psychological care for his problems, expect him to receive therapy in confinement. Had he lived at the film’s end, that is.

Ultimately, Eric Binford walked hand-in-hand with Cody Jarrett and failure on Hollywood Blvd.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/06/835/n/1922564/8e601b95681a5cf04194c6.14070357_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/05/05/100/n/1922564/33582ae7681964cb0d40c8.72464171_.png)

![ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge] ABYSMAL RITES – “Restoring The Primordial Order” [Heavy Sludge]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WHD581-600x330.jpg)